Expert Identification Problem

- Have a working conceptualization of "expertise" that has been critically analyzed

- Decide whether the predicate "is an expert" is applicable to this candidate

- Consult a collection of criteria that can help establish whether the candidate is an "expert"

The above classification is provided by scholars from the field of Argumentation Theory. This is a rich discipline that studies patterns of reasoning. One particular concept, that we will be invoking here to assess expertise, is the argumentation schematic. From Argumentation Schemes: History, Classifications, and Computational Applications, it is defined as:

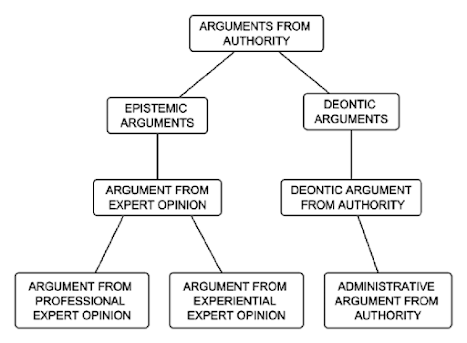

In other words, the schemes are like patterns or archetypes, that consistently occur within many domains of inquiry or dialogue. One particular pattern is the "Argument from Authority" or "Argument from Expert Opinion". These occur when someone needs to offload the process of justification onto a third party who presumably has done the work. In premise form, the argument looks like this (Walton, Appeal to Expert Opinion):... stereotypical patterns of inference, combining semantic-ontological relations with types of reasoning and logical axioms and representing the abstract structure of the most common types of natural arguments [Macagno and Walton, 2015]. The argumentation schemes provided in [Walton et al., 2008] describe the patterns of the most typical arguments, without drawing distinctions between material relations (namely relations between concepts expressed by the warrant of an argument), types of reasoning (such as induction, deduction, abduction), and logical rules of inference characterizing the various types of reasoning (such as modus ponens, modus tollens, etc.). For this reason, argumentation schemes fall into distinct patterns of reasoning such as abductive, analogical, or inductive ones, and ones from classification or cause to effect.

- Conditional Premise: If Source E is an expert in subject domain S containing proposition A, and E asserts that proposition A is true (false) then A is true (false).

- Major Premise: Source E is an expert in subject domain S containing proposition A.

- Minor Premise: E asserts that proposition A is true (false).

- Conclusion: A is true (false).

You can imagine that argument from authority can occur at any stage within these types of dialogues. The crucial point is that "expert identification" occurs within a circumstance constrained by pragmatic considerations where our knowledge is defeasible. We typically hear an argument from authority, and then must determine whether that person is indeed an authority, before accepting the conclusion of the interlocutor. Below are six basic critical questions of arguments from authority:

- Expertise Question: How credible is E as an expert source?

- Field Question: Is E an expert in the field F that A is in?

- Opinion Question: What did E assert that implies A?

- Trustworthiness Question: Is E personally reliable as a source?

- Consistency Question: Is A consistent with what other experts assert?

- Backup Evidence Question: Is E’s assertion based on evidence?

The first question concerns the depth of knowledge the expert supposedly has. Is the expert a master or only a beginner, even though he or she is qualified? This factor corresponds to the perceived expertise of the source, cited as one of the two most factors by Gilbert et al. (1998). The second question asks whether the field of the expert matches the field into which the proposition A falls. The third question probes into the exact wording of what the expert said (whether quoted or paraphrased). The fourth question raises doubts whether the expert is personally reliable as a source, for example, if she is biased, or has something to gain by making the statement. This factor corresponds to the trustworthiness of the source cited as the other of the two most important factors cited by Gilbert et al. (1998). The fifth question asks what kind of evidence the expert’s pronouncement is assumed to be based on. If asked what evidence the pronouncement is based on, an expert should be willing to provide such evidence, and if she does not, the argument based on her expert opinion defaults.

A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if the proponent demonstrates to the court that it is more likely than not that:(a) the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue;(b) the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data;(c) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and(d) the expert's opinion reflects a reliable application of the principles and methods to the facts of the case.

- Testability: “whether it [the evidence, theory or technique] can be (and has been) tested”

- Error Rate: “the known or potential rate of error”

- Peer Review: “whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication”

- General Acceptance: the “explicit identification of a relevant scientific community and an express

- determination of a particular degree of acceptance within that community”. (Daubert at 594)

- Control Standards: whether its operation has been subjected to appropriate standards of control

- Whether experts are “proposing to testify about matters growing naturally and directly out of research they have conducted independent to the litigation, or whether they have developed their opinions expressly for the purposes of testifying” [Daubert at 1317].

- Whether the expert has unjustifiably extrapolated from an accepted premise to an unfounded conclusion [with reference to Joiner at 146].

- Whether the expert has adequately accounted for obvious alternative explanations [with reference to Claar v Burlington13].

- Whether the expert “is being as careful as he would be in his regular professional work outside his paid litigation consulting” [Sheehan v Daily Racing Form Inc. 14 at 942].

- Whether the field of expertise claimed by the expert is known to reach reliable results for the type of opinion the expert would give [with reference to Kumho at 1175]. (FRE, Rule 702, notes; see also Owen 2002, 361–2)

- “the technique’s relationship to other techniques established to be reliable”

- “the non-litigation-related uses to which the method has been put”

- “whether he [the expert] has sufficiently connected his testimony with the facts of the case.” (Ibid.)

In short, the standard of reliability is not free of difficulties as a method for assessing expertise in real cases. Fact-finders are normally not experts in the scientific fields in which testimony is now so often offered as evidence in court. Then how are fact-finders to understand and assess expertise in the courtroom? An answer to this question will be given and defended in the following sections using an argumentation model of transmission of expert opinion evidence from a scientific inquiry to a different procedural setting, that of a legal trial.

In answering this “trust” question, fact-finders have to consider more questions from internal and external aspects. The internal question concerns scientific validity and reliability of evidence itself. Scientific validity, which depends on scientific principles and methods, aims at answering the question: does the principle support what it purports to show? Reliability aims at answering the question: does application of the principle produce consistent results?

According to Walton, courtroom fact finders can reference a decision tree like the one below:

For internal validity of scientific research, we can assess the credibility of an expert when evaluating their claims, using the internal credibility criteria provided by Rule 702 and the critical questions (seen below) provided by Walton. For external credibility however, it is a bit more difficult. According to Walton, "Schum (2001, 103) identifies three factors that need to be taken into account in assessing the credibility of a witness: veracity, objectivity, and observational sensitivity", but the problem is that expert bias can still arise due to personal and financial interest. There tend to be strong benefits when affiliated with powerful interest groups, such that it might be impossible to disentangle these motivations from the credibility of their claims. Affiliation with organizations like these tend to enhance their expertise in the eyes of the public as well, making it even more challenging to differentiate between the institutional bias that might alter expert opinions and unfiltered opinions. The External Credibility branch is generally not addressed by Rule 702. There are no rules that explicitly account for this form of credibility. I don't think Walton's critical questions directly address this issue either. As I mentioned above, I don't want to address this problem here since it's way too broad to tackle.

- 1.1 What is E’s name, job or official capacity, location, and employer?

- 1.2 What degrees, professional qualifications or certification by licensing agencies does E hold?

- 1.3 Can testimony of peer experts in the same field be given to support E’s competence?

- 1.4 What is E’s record of experience, or other indications of practiced skill in S?

- 1.5 What is E’s record

- 2.1 Is the field of expertise cited in the appeal a genuine area of knowledge, or area of technical skill that supports a claim to knowledge?

- 2.2 If E is an expert in a field closely related to the field cited in the appeal, how close is the relationship between the expertise in the two fields?

- 2.3 Is the issue one where expert knowledge in any field is directly relevant to deciding the issue?

- 2.4 Is the field of expertise cited an area where there are changes in techniques or rapid developments in new knowledge, and if so, is the expert up-to-date in these developments?

- 3.1 Was E quoted in asserting A? Was a reference to the source of the quote given, and can it be verified that E actually said A?

- 3.2 If E did not say A exactly, then what did E assert, and how was A inferred?

- 3.3 If the inference to A was based on more than one premise, could one premise have come from E and the other from a different expert? If so, is there evidence of disagreement between what the two experts (separately) asserted?

- 3.4 Is what E asserted clear? If not, was the process of interpretation of what E said by the respondent who used E’s opinion justified? Are other interpretations plausible? Could important qualifications be left out?

- 4.1 Is E biased?

- 4.2 Is E honest?

- 4.3 Is E conscientious?

- 5.1 Does A have general acceptance in S?

- 5.2 If not, can E explain why not, and give reasons why there is good evidence for A?

- 6.1 What is the internal evidence the expert used herself to arrive at this opinion as her conclusion?

- 6.2 If there is external evidence, e.g. physical evidence reported independently of the expert, can the expert deal with this adequately?

- 6.3 Can it be shown that the opinion given is not one that is scientifically unverifiable?

"It might be said that these critical questions codify some of the background information that is assumed by (or implicit in) the argument from expert opinion. As questions, they function to request the background information on which the success of the argument depends. As objections, they challenge the acceptability of the original argument until the additional information is found to be favorable (to the initial argument). As such, the central feature of critical questions is that, when they are posed, they act as undercutting defeaters (Pollock 1995) for the original argumentation. Until the questions are satisfactorily answered, the original argument is defective and unacceptable. Moreover, there is no burden of proof associated with posing these critical questions. The questions themselves do not have to be supported with reasons, or evidence that their answers are unfavorable to the proponent of the argument from expert opinion. Instead, it is up to the proponent to demonstrate that they can be answered. In effect then, while the argumentative result of a presumptive argument is to shift the burden of proof to an objector, the argumentative result of posing a critical question is to shift the burden of proof back to the proponent of the argument."

The legal criteria and critical questions can be seen as a checklist ,where the person asking the questions determines if the criteria is applicable, and if the candidate has satisfied the criteria. Walton provides three scenarios of possible responses when a criteria is applied:

- (i) the proponent shows that the criterion has been satisfied (direct answer).

- (ii) the proponent shows that the criterion is not relevant (indirect answer).

- (iii) the proponent shows that the criterion is not significant (indirect answer).

The first of the paradoxes is well-recognized within argumentation theory (Bachman 1995; Goldman 2001; Goodwin 1998; Jackson 2008; Willard 1990). On the one hand, the argument from authority becomes the fallacious argumentum ad verecundiam, as it stifles the independent examination of reasons, thus endangering one of the basic principles of rationality. Indeed, if autonomous, unfettered, and unbiased weighing of reasons is what rationality consists of, then reliance on external authority with its prêt-à-porter judgements undercuts reason. Blind obedience to religious authority of any creed and epoch is a specimen of the grave offence to reason committed by appeals to authority.14 On the other hand, in the complex world we live in, there is only so much we can learn via direct, first-hand perceptual experience and individual reflection. A vast majority of our knowledge is second-hand knowledge, derived from the testimony of others in the position to know—i.e., eyewitnesses, experts, educators, public authorities, etc. (Lackey 2008). We simply cannot reason without arguments from epistemic authority, be them arguments from expert opinion, from testimony, or otherwise from the position to know. Hence the first paradox: authority both appears to be an unreasonable form of argumentation and its very condition of possibility.

- (A) Arguments presented by the contending experts to support their own views and critique their rivals’ views. (Cf. consistency and backup evidence question)

- (B) Agreement from additional putative experts on one side or the other of the subject in question. (Cf. consistency and expertise questions)

- (C) Appraisals by “meta-experts” of the experts’ expertise (including appraisals reflected in formal credentials earned by the experts). (Cf. field and expertise questions)

- (D) Evidence of the experts’ interests and biases vis-à-vis the question at issue. (Cf. trustworthiness question)

- (E) Evidence of the experts’ past “track-records” (Cf. backup evidence and expertise question)

If part of "expert identification" relies on individual judgement, this implies better or worse modes of reasoning underlying any given assessment. For example, if we find ourselves motivated to classify someone as an expert, solely motivated by political partisanship, we should be aware of this confirmation bias and reassess if feasible. If we are motivated by "winning" rather than exploration of truth, if we cannot possibly conceive of the option that we might be wrong, then identification of genuine expertise will be distorted. This obviously implies we consult our own motivations and reasons for classifying a candidate as an expert. Are we simply using this person as leverage in an argument to defeat an interlocutor? This requires self reflection, something I take to be a necessary condition for the efficient application of the criteria we have been discussing so far. It also implies that we don't just assume that our interlocutor is motivated by pernicious reasons. All too often, people explain away expert opinion by reference to a global conspiracy. This is antithetical to critical thinking and should be avoided at all costs.

- Logical Consistency: The explanation must be logically coherent and free from contradictions.

- Causal Adequacy: The explanation should properly account for the causal relationships that produce the phenomenon in question.

- Scope: The explanation should account for a wide range of phenomena, not just a single occurrence or a small set of cases.

- Simplicity: Sometimes referred to as "parsimony," the explanation should not be more complex than necessary.

- Unification: The explanation should unify different observations or facts under a single framework or theory.

- Falsifiability: The explanation should be testable and potentially refutable by empirical evidence.

- Observation: There is a set of observed facts or evidence (E).

- Hypotheses: There are multiple competing hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, …, Hn) that could explain these facts.

- Comparison: Each hypothesis is evaluated against a set of criteria (coherence, scope, simplicity, etc.).

- Selection: The hypothesis that best meets these criteria is inferred to be the most likely explanation.

Is the explanation that is proposed genuinely explanatory?

- Does the hypothesis offer a meaningful explanation for the observed data or evidence?

- Does it merely describe the evidence, or does it provide an underlying mechanism or cause?

Is the explanation coherent and logically consistent?

- Does the explanation avoid internal contradictions?

- Does it align with established facts and other accepted theories?

Does the explanation adequately account for all the relevant evidence?

- Does the explanation cover all the data or phenomena in question?

- Are there any significant pieces of evidence that the explanation fails to address?

Is the explanation more plausible than its competitors?

- Does the explanation make fewer assumptions than alternative explanations?

- Does it rely on reasonable and likely premises?

- How does it compare to other plausible explanations in terms of simplicity, scope, and power?

Is the explanation empirically testable or falsifiable?

- Can the explanation be empirically tested or verified?

- Are there predictions that could, in principle, disprove the explanation if they turn out to be false?

Is the explanation specific and detailed rather than vague or overly general?

- Does the explanation provide a clear, specific account of the phenomenon?

- Are the mechanisms it posits well-defined?

Does the explanation avoid ad hoc hypotheses?

- Does the explanation introduce new, unsupported assumptions to save itself from being discredited?

- Are there arbitrary additions to the explanation that make it less likely?

Does the explanation fit well with background knowledge?

- Is the explanation consistent with what is already known about the world?

- Does it contradict well-established scientific theories or empirical data?

- Is the hypothesis consistent with well-established theories, principles, or facts?

- Does it contradict what is already known, and if so, does it provide a compelling reason for such a contradiction?

Does the explanation have predictive power?

- Does the explanation allow for accurate predictions of future events or phenomena?

- Can it explain other related phenomena that were not originally considered?

Does the explanation have explanatory depth and breadth?

- Does it not only explain the current evidence but also provide insight into other related phenomena?

- Does it have the potential to unify disparate observations under a common framework?

Is the explanation conservative?

- Does the explanation fit well with our prior knowledge and does it not require a radical revision of our understanding?

Is the explanation simple and parsimonious?

- Does the explanation avoid unnecessary complexity and assumptions?

- Is it the simplest explanation that accounts for all the evidence?

Is the explanation testable or falsifiable?

- Can the hypothesis be subjected to empirical testing or verification?

- Is it possible to identify evidence that could, in principle, falsify the hypothesis?

Is the explanation robust across different contexts or evidence?

- Does the hypothesis hold up well under different conditions or when new evidence is presented?

- Does it remain plausible when subjected to scrutiny from multiple perspectives?

CQ1: How satisfactory is E as an explanation of F?

- This question evaluates how well the hypothesis explains the observed facts. It questions whether the hypothesis is actually a good fit for the evidence.

CQ2: How much better an explanation is E than the alternatives?

- This checks whether other possible explanations have been considered and whether the current explanation is truly superior.

CQ3: How thorough is the search for alternative explanations?

- This question challenges whether a wide enough range of potential explanations has been considered. If alternative hypotheses have been overlooked, the conclusion might be premature.

CQ4: How likely is it that E is true, as opposed to other possible explanations?

- This critical question deals with the probability or plausibility of the explanation being true, relative to other explanations.

CQ5: Could F be explained by a combination of multiple factors?

- This question examines whether the facts could be explained by more than one cause or factor rather than a single explanation. This would challenge the sufficiency of the current hypothesis.

1. Clarify the Evidence and Observation

What is the evidence the expert is explaining?

Start by identifying the specific observations or data that the expert is trying to explain. This helps to anchor the argument and makes it easier to assess whether the proposed explanation is truly the best.Does the expert provide a clear account of the facts?

Ensure that the evidence being discussed is presented accurately, clearly, and comprehensively. Are they using all the relevant evidence, or is some important data being overlooked or ignored?

2. Check the Explanation’s Coherence and Plausibility

Is the expert’s explanation coherent and logically sound?

A good abductive argument should be internally consistent. Does the expert's explanation make sense, or are there contradictions within their reasoning?Does the explanation fit with what we already know?

The explanation should be consistent with existing theories, knowledge, or data unless there’s strong evidence to challenge the established framework. Is the expert proposing something that goes against well-established facts without sufficient justification?

3. Evaluate Competing Hypotheses

Has the expert considered alternative explanations?

Even though an expert may be focused on one explanation, good abductive reasoning involves comparing multiple hypotheses. Did the expert consider alternative possibilities, and if so, why were those alternatives rejected? Is the reasoning for rejecting them sound?Is the proposed explanation the best among alternatives?

Just because an explanation fits the data does not mean it is the best explanation. Is the expert's explanation superior to other hypotheses in terms of simplicity, explanatory scope, or fit with the evidence?

4. Check for Testability and Predictive Power

Can the expert’s explanation be empirically tested?

One of the hallmarks of a strong explanation is its ability to be tested or falsified. Ask whether the expert's hypothesis allows for empirical verification or whether it makes predictions that can be tested against future evidence.Does the explanation make new predictions?

A strong abductive explanation will often predict new facts or phenomena. Does the expert’s explanation lead to any new insights or predictions that can be verified?

5. Assess Simplicity and Parsimony

Is the expert’s explanation unnecessarily complex?

According to Occam’s Razor, a simpler explanation that accounts for all the evidence is preferable to a more complicated one. Is the expert introducing unnecessary complexity, or is their explanation concise and to the point?Are there ad hoc assumptions?

Check whether the expert is introducing arbitrary or unsupported assumptions to make the explanation fit. An ad hoc adjustment can weaken an abductive argument, suggesting the hypothesis might not be as strong as it first appears.

6. Consider the Expert’s Bias and Motivations

Could the expert be biased in their reasoning?

Experts, like anyone else, can be subject to confirmation bias or other cognitive biases. Are there any indications that the expert is favoring a particular explanation due to personal biases, institutional pressures, or vested interests?Is there over-reliance on authority?

Just because an expert endorses a particular explanation doesn't mean it should be accepted without scrutiny. Are they appealing to their authority rather than making a well-reasoned argument supported by evidence?

7. Review the Scope and Breadth of the Explanation

Does the explanation account for all the relevant data?

Ensure that the expert’s argument covers all the known facts. Are there any key pieces of evidence that are being ignored or downplayed because they do not fit the proposed hypothesis?Does the explanation unify disparate observations?

A good abductive explanation often has the power to unify various observations or phenomena under a common framework. Does the expert’s explanation provide a broader understanding that could explain other related facts or situations?

8. Examine the Explanatory Power

How well does the explanation clarify the evidence?

An abductive argument should help clarify the evidence or make it more understandable. Does the expert's explanation provide a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, or does it leave key aspects unexplained?Does the explanation resolve anomalies?

If there are anomalies or unexpected findings, does the expert’s explanation satisfactorily address them? Strong abductive arguments often explain surprising or puzzling data better than alternatives.

9. Consider the Domain-Specific Expertise

Is the expert working within their field of expertise?

Ensure the expert’s abductive argument falls within their domain of expertise. Even experts can make errors when reasoning outside their field, and expertise in one area does not necessarily translate to others.Do they use technical knowledge appropriately?

Evaluate whether the expert is applying their technical knowledge correctly. Are the scientific or technical concepts being used accurately, or are there misunderstandings or misapplications?

10. Evaluate the Strength of the Evidence

Is the evidence reliable and sufficient?

A strong abductive argument depends on solid, well-supported evidence. Is the expert relying on high-quality data, or is the evidence weak, anecdotal, or incomplete?Are there any unstated assumptions or missing evidence?

Scrutinize whether the expert is making any unstated assumptions that could undermine the argument. Also, consider whether there is missing evidence that, if known, might alter the conclusion.

- Explanations Justify Recommendations: When someone makes a recommendation, they are often implicitly or explicitly providing reasons or explanations for their suggestion. For instance, a doctor might recommend a specific treatment because of its effectiveness, explaining that it has fewer side effects than alternatives. A strong recommendation is grounded in an explanation that makes clear why it is better suited to a person’s needs, preferences, or situation.

- Evaluating Recommendations Involves Examining Explanations: To assess the quality of a recommendation, one must examine the explanation behind it. This includes evaluating the logic, evidence, and assumptions that support the recommendation.

Clarity and Logic of the Explanation: Does the recommendation come with a clear explanation? Is the reasoning behind the recommendation sound and logical? For instance, if someone recommends a particular investment strategy, does their explanation lay out the financial benefits, risks, and long-term expectations in a coherent way?

Evidence and Supporting Information: Is there sufficient evidence or data to support the recommendation? Are the explanations based on reliable facts, studies, or expert opinions, or do they rely on anecdotal information? A doctor recommending a treatment should be able to cite clinical trials, medical research, or case studies to support their recommendation.

Consideration of Alternatives: Does the recommendation consider alternatives and explain why they were not chosen? A strong recommendation should show an awareness of other options and explain why the proposed course of action is superior. If someone recommends a particular university, do they also discuss why other universities might be less suitable based on factors like location, cost, or academic offerings?

Context Appropriateness: Does the recommendation fit the specific context and needs of the individual? Even a well-reasoned recommendation might not be appropriate if it doesn’t align with the person’s particular circumstances, goals, or values. For example, recommending a high-intensity workout routine to someone with a history of joint problems might not be appropriate, even if it's generally effective for fitness.

Potential Bias or Conflicts of Interest: Is there any bias in the recommendation? Does the person making the recommendation have a vested interest in the outcome? For example, if a financial advisor recommends a particular stock but receives a commission from its sale, this potential conflict of interest could affect the credibility of their recommendation.

Feasibility and Practicality: Is the recommendation realistic and practical to implement? Sometimes a recommendation might be theoretically sound but impractical given the available resources, time, or capabilities of the person receiving it. For instance, recommending an elaborate meal plan for someone with a busy schedule might not be feasible, even if it’s nutritionally ideal.

Track Record and Reputation: What is the track record or expertise of the person making the recommendation? Evaluating their qualifications and previous successes or failures can provide insight into the reliability of the recommendation. An IT consultant with years of experience and a strong reputation might offer more trustworthy recommendations than someone less familiar with the field.

Comments

Post a Comment