The Nature of Agnosticism: Part 4.3

This is a continuation of the topic "what causes religious belief". So far we have been analyzing mechanisms internal to theistic belief systems that cause them to persist. This is a continuation of that analysis.

The Role of Story Telling

This is somewhat obvious at first, given that scripture is just one big story (hearsay specifically). But it’s a bit deeper than imagined on second glance. Story telling is paramount in religion. It extends directly from the notion of metaphor, because what good is a metaphor without a guiding story that contains temporal ordering, directing the adherent to some end. I don’t just mean stories in the abstract sense; I also mean stories in the form of “testimonials” such as near-death experiences and encounters with “god working in someone’s life”. These minor stories serve to bolster the grander narrative told by scripture. They act as mechanisms supporting the much larger world view, among other story-like literary devices such as allegories and parables.

There are some good papers identifying the effect of narrative on our belief formation. They show that the more transported we are in a narrative, the less likely we are to identify inconsistencies or other errors in the story. We are also much more likely to adopt the narrative, resonating with the characters and seeing the world through that lens, even if there was false information. In addition, there tends to be a sleeper effect, meaning that weeks later there will be a stronger degree of conviction. I’ll post the papers and their abstracts here, then after briefly discuss the implications.

The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives:

Transportation was proposed as a mechanism whereby narratives can affect beliefs. Defined as absorption into a story, transportation entails imagery, affect, and attentional focus. A transportation scale was developed and validated. Experiment 1 (N = 97) demonstrated that extent of transportation augmented story-consistent beliefs and favorable evaluations of protagonists. Experiment 2 (N = 69) showed that highly transported readers found fewer false notes in a story than less-transported readers. Experiments 3 (N = 274) and 4 (N = 258) again replicated the effects of transportation on beliefs and evaluations; in the latter study, transportation was directly manipulated by using processing instructions. Reduced transportation led to reduced story-consistent beliefs and evaluations. The studies also showed that transportation and corresponding beliefs were generally unaffected by labeling a story as fact or as fiction.

Persuasive Effects of Fictional Narratives Increase Over Time:

Fact-related information contained in fictional narratives may induce substantial changes in readers' real-world beliefs. Current models of persuasion through fiction assume that these effects occur because readers are psychologically transported into the fictional world of the narrative. Contrary to general dual-process models of persuasion, models of persuasion through fiction also imply that persuasive effects of fictional narratives are persistent and even increase over time (absolute sleeper effect). In an experiment designed to test this prediction, 81 participants read either a fictional story that contained true as well as false assertions about real-world topics or a control story. There were large short-term persuasive effects of false information, and these effects were even larger for a group with a 2-week assessment delay. Belief certainty was weakened immediately after reading but returned to baseline level after 2 weeks, indicating that beliefs acquired by reading fictional narratives are integrated into real-world knowledge.

Several studies show that religion hinders concerns for the natural environment preservation. Others, however, have found that the belief in God or the identification with a particular religion is not associated with measures for environmental concerns. This study investigates the influence of religious narrative framing and the relation between Allport’s intrinsic personal (IP) and extrinsic social (ES) religious orientation towards general environmental apathy (GEA) and acceptability for harming animals (AIS). This study surveyed 657 teachers and school staff in East Java, Indonesia. Using ANOVA, we find that religious narrative affects participant’s GEA and AIS. Participants in stewardship narrative group have significantly lower GEA and AIS compared to participants in human dominance and the non-narratives control group. Using multiple regression, we also confirm the persistence of religious narrative’s influence towards GEA. In addition, lower GEA and AIS correlate with higher IP and lower ES. Lastly, we identify and discuss significant demographic and other determinants relation to GEA and AIS.

Effects of narrative transportation on persuasion: A meta-analysis:

The impact of narrative transportation on persuasion continues to attract research attention (e.g., Escalas 2004; Escalas 2007; Green and Brock 2000, 2002; Slater and Rouner 2002). When consumers lose themselves in a story, their attitudes and intentions change to reflect that story (Green 2008). Since Green and Brock (2000) initiated quantitative transportation research, many studies have investigated narratives, how they transport consumers, and how they change consumers' views. Furthermore, recent developments have enhanced the significance of transportation effects, including interactive video games (Baranowski et al. 2008), narrative advertising (Chang 2009), and reality TV (Hall 2009). Thus, transportation demands theoretical and applied research attention (Singhal and Rogers 2002).

The impact of narrative persuasion depends on the location of its persuasive information relative to the cause-and-effect structure within the narrative, yet, the bounds of this structural influence remain unknown. This study examines the a) underlying psychological mechanism, b) strength in overcoming psychological resistance, and c) persistence over time of narrative causality effects on information acceptance. Results suggest causality effects occur during initial stages of comprehension, which serve to shield the influence from external moderators, such as preexisting worldviews. The effect also remained constant over a two-week delay. Results serve to psychologically explain the narrative causality effect and suggest it remains robust over a wide range of conditions, potentially being useful for persuasion of otherwise resistant audiences.

This research empirically tests whether using a fictional narrative produces a greater impact on health-related knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intention than presenting the identical information in a more traditional, nonfiction, non-narrative format. European American, Mexican American, and African American women (N = 758) were surveyed before and after viewing either a narrative or non-narrative cervical cancer-related film. The narrative was more effective in increasing cervical cancer-related knowledge and attitudes. Moreover, in response to the narrative featuring Latinas, Mexican Americans were most transported, identified most with the characters, and experienced the strongest emotions. Regressions revealed that transportation, identification with specific characters, and emotion each contributed to shifts in knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions. Thus, narrative formats may provide a valuable tool in reducing health disparities.

All these papers indicate a strong relationship between belief formation and narrativity. The last paper is very interesting because it suggests that narratives can be tailored to achieve optimal goals. However, it can be harmful as in the cases of environmental awareness and marketing. Therefore, it should be no surprise that this is the most common technology religions use to retain adherents. The language of faith is not the language of scientific inquiry. Every week when people come to congregation, they have no intention on critically assessing the content against a systematic set of criteria designed to reduce bias. Quite the contrary, if someone does express critical doubts about the content, they are met with disapproval. This is why I’ve been trying to show that belief formation is completely independent of logical reasoning and evidence. Most Christians are completely unaware of the philosophical roots of the contingency argument for example. They did not come to belief because of the “similarities between DNA and computer code”. This is all after the fact. The main source of inspiration comes from these stories. Religion lives in stories, parables, allegories, heroic narratives, and testimonials. All of this is told with extreme passion. I’ve experienced this myself. I’ve come across pastors that are very dull and boring, but the ones that are incredibly passionate (like black gospel) are much more inviting. I’ve come across English Anglican priests who have incredible speaking abilities, captivating the audience. Theists are transported by these modes of expression. When transported, many ideas can be inserted into our minds without us knowing and without any resistance. There is no critical questioning. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. I’ve literally seen passionate outbursts of emotion such as crying and anguish when people retell the story of the resurrection. The audience is invited to feel what the apostles allegedly felt. But of course, theists are taught to be hypercritical and detached when hearing the narratives of other religions.

Consider “Christian Witnessing”. This involves “testifying” to others about your experience with god. To testify in this context means to share a story about some experience or encounter you had. There will typically be religious significance to the story and people are encouraged in many denominations to share, citing 1 Peter 3:15 to as the reason. People in ministry give instructions on how to structure these stories, as seen in this video: How to Share Your Personal Testimony. There are workshops There are workshops where they train Christians how to profess to others in hopes of converting people to Christianity. There are literal blog posts about the virtue of storytelling, they literally advocate and teach people how to effectively craft narratives: Sharing Our Testimonies: The Power of Story in Your Ministry. You can see this everywhere if you’ve ever attended a church, especially in protestant denominations. Charismatic speakers will share personal experiences of what they think is god. One really caught my attention. A pastor once shared their experience about how they, and others from the community, joined together weekly for prayer and singing. This happened in a very poor and violent town in Central California called Fresno. If you are unfamiliar with the Central Valley you should read up a bit because it is notorious for being poor, uneducated, and dangerous; coincidentally also one of the most religious regions in the state. Anyways, as with all these testimonials, there are never any specific details mentioned for the audience to verify. The storyteller always abstracts these away “one time, at this one place, with that one person” because obviously, providing details will potentially falsify the experience. Anyways, the pastor described an experience of how simple prayer led to increased economic prospects for the community, and that the rate of violent crimes decreased. This shows how the power of prayer can work in large groups and that the holy spirit works for those who are faithful. I am not quite sure what went through the congregations’ head, but I did not passively accept this. I am also from the Central Valley region and have studied developmental economics. It’s quite interesting to me that this miracle somehow missed my radar and that massive economic programs are completely irrelevant when it comes to lifting towns out of poverty. Apparently, all you need to do is pray. Obviously, this is bullshit. But the key point here is that unsubstantiated causal claims go unchecked by participants in the congregation very frequently. Stories are not critically assessed. In fact, it would be somewhat rude to question the witness; this tends to be a social convention. I’ve encountered another Christian who originally came from Africa. He was describing a story about the power of Jesus in fighting off evil spirits. There was a far-fetched story about how someone in the village was a witch doctor of some sort who used her powers by summoning demonic forces. She could not control these forces (obviously), so they began running amuck. A “true Christian believer” came to the rescue, calling on the “Word of God”, scaring the demons off and bringing back peace to the village. The other Christians in the room rightly seemed a bit skeptical, but who are they to question the veracity of the story? This is what I mean when I said there’s a social convention around automatically believing the “testimonials” of other believers. This form of on-the-ground story telling is incredibly powerful because Christians will tend to accept most of these stories uncritically.

There is something quite interesting about the structure of these stories. As mentioned above, ministers will train Christians on how to “witness” to others. There is the BC-D-AD model, standing for Before Christ-Decision-After Decision, where you are encouraged to focus on the positive benefits after “making your decision to convert”. I quote this phrase because it’s quite hilarious to think that people are independently deciding to convert without a lifetime of pre-conditions enabling the option. Multiplying Disciples is another website dedicated to providing methods to believers that teach how to convert other people. This includes how to properly share a testimony. It follows a similar template to what we have covered so far: you were in darkness, you found Christ, now you are at peace. It’s interesting because they use methods from sales, marketing, and rhetoric to achieve their goals. Like marketing, these stories also have a purpose. For non-believers it’s to convert them. For believers it’s to retain and reassure them. Testimonials boil down to claiming something miraculous happened when the audience is Christian. When the audience is composed of non-believers, it boils down to “God saved you, God made your life better, and god can do the same for anyone who ‘truly’ accepts him”.

My point with this section is that stories are the propellers that keep religious belief in perpetual motion. We know that stories have an incredible impact on human belief formation. It’s no wonder that religious institutions use this as a prime method in their daily functioning. But there is always an asymmetry. Consider the countless number of religious testimonials a Muslim could generate. Consider also all of the testimonials from non-christians and ex-christians who profess the utter absence of god, or who have alternative explanations for the alleged experiences. It’s highly likely the Christian will dismiss these. This is what happens when you’re saturated in a dogmatic narrative that cannot handle dissenting testimony. I mean just imagine if on a Sunday I lined up to give my testimony. I am slotted to be next, after the ultra-charismatic person who came before me talks about how Jesus transformed his life. Then I got the microphone….

Stories have transformative effects, but there is a downside. As mentioned above in the article describing the impact of story on environmental awareness, adopting stories can blind us to reality because we dismiss evidence in favor of story consistency. Biblical stories caused people to see disease as a curse, to see seizures as demons, to believe witches exist (Exodus 22:18) and commanded us to murder them. They cause Christians to see themselves as the persecuted class despite living in a nation with a Christian supermajority. They cause us to see rational deliberation, discussion, and dialogue with interlocutors as threats who are only trying to undermine your faith. They cause us to see people as nothing more than things we need to convert. Paradoxically, they cause us to see people struggling with their faith as “not true Christians” who just want to sin. They cause is to question whether we are fundamentally flawed for not experiencing the pre-canned testimonials experienced by those true Christians. Stories can give you a sense of certainty and direction, but throughout human history our advances in knowledge come when we abandon narratives in favor of rigorous empirical investigation. These discoveries tend to be unfavorable, since there is a reconciliation process needed to incorporate the knowledge into the story, ultimately causing cognitive dissonance if the facts cannot be reconciled by the narrative.

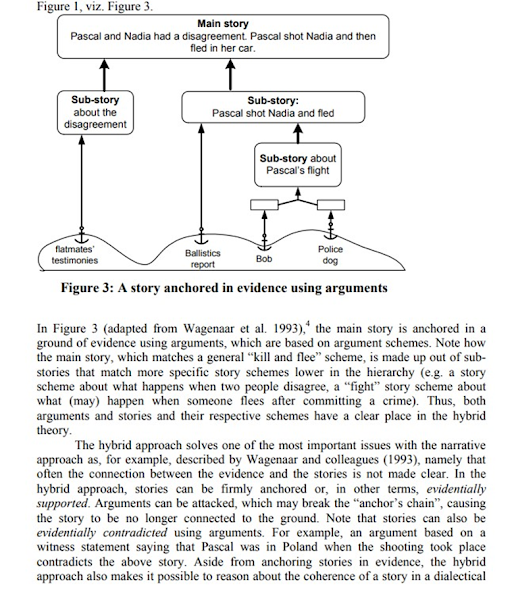

In the section on metaphor, I listed some argumentation schemes and corresponding critical questions that would help identify and challenge the analogy. I’ll do the same here because different schemes tend to be implicit in story structure. I am getting this material from “Arguments, Stories and Evidence: Critical Questions for Fact-finding by “Floris Bex and Bart Verheij. These are used to assess facts and evidence in criminal cases, but I think they extend to other domains as well. They combine two frameworks: the argumentative framework and the narrative framework. In the argumentative framework, facts need to be supported by reasons based on evidence. The narrative approach involves presenting these facts as stories, coherent descriptions of what happened, that causally explain as much of the evidence as possible. Critical questions on this approach revolve around coherence and quality of the story, and how to choose among competing stories (story comparison):

“In this paper we will show that a strong analogy can be drawn between reasoning patterns in argumentation, the familiar argumentation schemes (Walton et al. 2008), and patterns in the narrative approach, which we call story schemes (Bex 2009). These story schemes act as a background for particular instantiated stories in the same way as argumentation schemes act as a background for particular instantiated arguments. Furthermore, story schemes give rise to relevant critical questions in the same way as argumentation schemes.”

Rather than summarizing the paper I’ll just post the hybrid model described by the authors. The idea is that evidential data in a case should be causally explained by hypothetical stories through abductive inference.

“The basic idea of abductive inference (see e.g. Walton 2001) is that if we have a general rule ‘c is a cause for e’ and we observe e, we are allowed to infer c as a possible hypothetical explanation of the effect e. This cause c which is used to explain the effect can be a single state or event, but it can also be a sequence of events, a story.”

On the narrative approach, we assess story coherence and plausibility based on these abductive inferences, inference to best explanation, and general common-sense knowledge about the causal relations in the world. For example, there must be a coherent chronological arrangement of the alleged events. They must be consistent with the motives, goals, and actions we typically would expect of the characters in the story. The events and transitions between the events must cohere and be somewhat aligned with how things normally work. If parts of the story are missing, this could affect the coherence and plausibility of the explanation.

“Experiments by Pennington and Hastie (1993) suggest that when reasoning with a mass of evidence, people compare the different stories that explain the evidence instead of constructing arguments based on evidence for and against the facts at issue (as is done in the argumentative approach). However, a disadvantage of the more holistic narrative approach is that the individual pieces of evidence do not always have a clear place and the evidence’s relevance with regards to the facts at issue cannot be checked easily. Furthermore, it is not always clear how one should reason about the coherence of a story and how stories should be compared.”

Hence, the combination of the two approaches. We need to critically assess individual facts anchoring the narrative, while also checking whether the story is consistent and plausible. The anchoring analogy is crucial. If there are no facts anchoring the story, what are we to make of it? The hybrid approach also recognizes that stories aren’t mere collections of facts. They need to be explained. There could be many explanations consistent with the data. From the article:

Here is how we would critically assess an alleged fact in isolation from the story: The argument from witness testimony.

- Witness w is in a position to know whether a is true or not.

- Witness w asserts that a is true (false).

- Therefore, a may plausibly be taken to be true (false).

Critical Questions

- Was w is a position to know a?

- Is w truthful?

- Is w biased?

- Is w’s statement that a internally consistent?

- How plausible is w’s statement that a?

- Is a consistent with what other witnesses say?

- (CQ1) Are the facts of the case made sufficiently explicit in a story? A case should contain a clearly phrased, sufficiently specified and coherent story detailing “what happened”.

- (CQ2) Does the story conform to the evidence? a. Is the story sufficiently supported by the evidence in the case? b. Is the story contradicted by evidence in the case? In general, not all elements of a story can be supported by evidence. This does not need to be a problem, and is in fact unavoidable as certain story elements must by their nature be indirectly justified. When an element of a story is not supported by a piece of evidence (in a given argument), we speak of an 'evidential gap'

“The existence of evidential gaps, here conceived of as parts of a story for which no direct evidence is available, is one reason why a mixed-argumentative narrative perspective can be useful. The analytical argumentative perspective makes the evidential gaps visible, the narrative perspective shows why the evidential gaps can still be believed in conjunction with other facts. In general, it is a matter of good judgment which elements of a story must be directly supported by evidence and which can be inferred from other facts. This depends in part on the quality of the evidence (a story supported by weak evidence can become stronger by providing evidence for more facts), but also on the nature of the crime and the law. In addition to looking at how much of the story is supported, one should also consider how much of the total evidence in the case supports the story. If, for example, a story is completely supported by 2 witness testimonies but there are 20 more witnesses who state another (incompatible) story, the story does not sufficiently conform to the evidence in the case even though there are no gaps in it. Furthermore, one should also take into account the amount of evidence that directly contradicts a story; instead of giving an alternative story (see CQ5 below), the opposing party may simply deny elements of the main story.”

- (CQ3) Is the support that the evidence gives to the story sufficiently relevant and strong? a. Are the reasoning steps from evidence to events in the story justified by warranting generalizations and argument schemes that are sufficiently strong and grounded? b. Are there exceptions to the use of the generalizations and schemes that undermine the connection between evidence and fact?

- (CQ4) Has the story itself been sufficiently critically assessed? a. Is the story sufficiently coherent? Are there required elements missing? Are there implausible events or causal relations? Is the story inconsistent? b. Have story consequences been used to test the story?

“First, the story's coherence must be examined (CQ4a). Here coherence has a specific meaning, namely that the story fits our knowledge and expectations about the world we live in. In other words, a story should be complete (i.e. have all its essential parts) and plausible (i.e. have plausible causal relations). A further way of testing a story is to look for possible reasons against facts that follow from the story (story consequences, CQ4b).”

- (CQ5) Have alternative stories been sufficiently taken into account? a. Has a sufficient search for alternative explanations been performed, not only in the investigative phase, but also in court? b. Are there good reasons to choose one story over the alternatives? Have the alternatives been sufficiently refuted?

“First a serious search for alternative scenarios is needed. In part, the opposing party in the process will provide alternatives, but a decision maker will also have to actively consider different accounts of what may have happened. These alternatives should not only be actively sought, they should also be adequately refuted: essentially, all the critical questions that can be asked for the main story also have to be asked for the alternatives.”

- (CQ6) Have all opposing reasons been weighed? Have all considerations that are used to weigh opposing reasons been made explicit? Has this been done both at the level of individual facts and events and at the level of stories?

- The prosecution must present at least one well-shaped narrative.

- The prosecution must present a limited set of well-shaped narratives.

- Essential components of the narrative must be anchored.

- Anchors for different components of the charge should be independent of each other.

- The trier of fact should give reasons for the decision by specifying the narrative and the accompanying anchoring.

- A fact-finder's decision as to the level of analysis of the evidence should be explained.

- Through an articulation of the general beliefs used as anchors.

- There should be no competing story with equally good or better anchoring.

- There should be no falsifications of the indictment's narrative and nested sub-narratives.

- There should be no anchoring onto obviously false beliefs.

- The indictment and the verdict should contain the same narrative.

“Doubt as sin. — Christianity has done its utmost to close the circle and declared even doubt to be sin. One is supposed to be cast into belief without reason, by a miracle, and from then on to swim in it as in the brightest and least ambiguous of elements: even a glance towards land, even the thought that one perhaps exists for something else as well as swimming, even the slightest impulse of our amphibious nature — is sin! And notice that all this means that the foundation of belief and all reflection on its origin is likewise excluded as sinful. What is wanted are blindness and intoxication and an eternal song over the waves in which reason has drowned.”

“So it was that I turned my attention to the concept that had allowed all these contradictions to accumulate; the concept that had anesthetized my enquiring mind: 'Faith is a virtue'. This assertion had come to feel so monolithic and indisputable. But now the simple truth was revealed: No it isn't. The concept of faith tried to arouse and exploit the kind of protective loyalty we might feel towards loved ones. in whose goodness we trusted. But I realized that the trust we invest in loved ones was based on very different principles. Trust in humans was earned. We believed in the goodness of loved ones because we had direct experience of their goodness. Religious faith was not earned — it was simply demanded based on a stack of bold claims that were never substantiated. In fact, bizarrely, if direct evidence was ever offered, faith would become instantly redundant. Faith, by its very nature, was forced to reside in the ambiguous, the circumstantial relying purely on the believers' conviction that their inferences were correct. Faith differed from trust in another key respect: if a loved one was accused of a transgression that contradicted our good opinion we'd want to see evidence — in fact, we would demand it. but with religious faith all contradictory evidence was dismissed as invalid right from the start on the assumption that if you took the time to investigate it properly it would turn out to be false. It was as I contemplated this last point further that I experienced one of the creepiest moments in my exploration — when I realized that what I was looking at here was the perfect system for protecting lies. Faith required that you believe despite an absence of expected evidence or despite the presence of conflicting evidence. But how do we detect lies? Through the absence of expected evidence or the presence of conflicting evidence. The very things that faith demanded we disregard. Any supreme intelligence would know that a system that protected lies so efficiently Would lay humans open to just about any conceivable abuse. People could be manipulated to accept all kinds of deceptions. those who complained about inconsistencies could be silenced by the devastating accusation that their faith wasn't strong enough. No supreme intelligence would entertain such a perverse concept as faith unless that intelligence was itself perverse.”

"I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to. ... Now it seems to me obvious that He was neither a lunatic nor a fiend: and consequently, however strange or terrifying or unlikely it may seem, I have to accept the view that He was and is God."[12]

- The Abrahamic God exists.

- Jesus existed

- The Gospels are an accurate record of Jesus' life and teachings

- Jesus (and people in general) are of homogenous character and cannot contain contradictory or opposing aspects within their person.

- Jesus himself claimed to be God.

- If Jesus existed, it is assumed that all the sayings attributed to him were by him. If the preachings of many men were attributed to Jesus, some may have been mentally unstable and/or liars.

- Any false accounts could have been added to the narrative during the decades of oral transmission before the Gospels were written down.

- Everything about the accounts must be “lies” or “the truth”. There is no room for nuance; there must be a dichotomy. Perhaps some of the sayings are truthful, some are lies, and some are mistakes.

- There is no contrary material that could call into question the veracity of the claims made in the bible. For example, there is an implicit assumption that Jesus didn’t recant. We know this is possible but given motivational reasons to disregard source material running contrary to the theological assumptions, contrary source material was destroyed in the canonization process. In other words, you must assume the process was unbiased and non-selective.

- Myths or legends surrounding the events of Jesus couldn’t possibly emerge during the oral transmission of the stories cross culturally and cross generationally. You must assume that the gospels are historical recordings, rather than tales that spread over a social network. This is highly dubious.

- During the initial spread of the religion, you must assume that there was nothing to gain by claiming the founder of the religion was divine. Some people try and defend this view by pointing out the “Apostles died for the cause”. This is yet another absurd argument that has been addressed elsewhere: Did the Apostles Die for a Lie?

- You must assume that every other story of divinity is myth or legend, despite sharing numerous similarities with the biblical account. You must assume that, all of the other religions are liars.

- You must assume that the bible cannot contain any embellishments or exaggerations. There also can be no such thing as honest mistakes.

- Jesus was honestly mistaken. He was still intelligent, sane, and wise in some cases. For example, Alexander the Great and the Caesars, honestly believed themselves to be divine and we consider them intelligent. Back in the day, people were incredibly superstitious, claiming to have all sorts of alleged connections to the supernatural. Given the cultural context, these claims were by no means considered insane.

- Jesus was politically savvy, proclaiming divinity for political purposes. It was not uncommon for leaders to claim divinity when establishing political or religious movements, similar to how people claim the status of King despite not being institutionally legitimized, to gain a following.

- Jesus was not lying, but the people recording the events of the gospels were lying. It is universally agreed that we have no direct writings from Jesus. It is completely possible that these people were lying or delusional. They could have also simply been mistaken. Given that the stories were being passed around orally for decades before transcription, it’s possible they misheard, misremembered, or deliberately altered the contents of the story. Furthermore, we know that stories tend to become more embellished over time when repeated orally without any sort of quality assessments. Given the context of Judea, it’s not implausible to suggest that divinity was attributed to Jesus by word of mouth.

Why are there so many bad arguments? Why is critical examination suppressed? As I mentioned earlier, it’s due to how “doubt” is conceptualized in these communities. Doubt is seen as something dangerous, disloyal, or destructive. Apologetics exists to contain possible doubt, among other social mechanisms such as shame and guilt. But this is a very warped view of doubt, which begs the question; who does this serve? Doubt can literally help you identify faults, flaws, and inconsistencies that could have devastating effects if overlooked. Exercising your critical faculties helps you identify instances of manipulation. Doubt is what literally allows us to discern truth from false claims, to see nuance in complex situations, and assess multiple conflicting decisions. The religious institutions have it backwards. They see doubt as something that leads you away from the (unsubstantiated) truth they dogmatically assert. They conceive of it as a tool used by the enemy (Satan) that “draws you away from god”. What happens when you are drawn away from god? Divine wrath that will take place in the unsubstantiated afterlife. What happens when you begin to question the veracity of the religious experiences people are allegedly having? Social ostracization. These are incredibly strong mechanisms that highly disincentivize and discourage the act of doubting, despite its benefits.

Remember that Faith is the ultimate good. Doubt is typically characterized as the antithesis of Faith. While simultaneously, Faith is synonymous with Obedience. Jesus did say that “to love him is to follow his commands”, meaning you must obey. It’s a very nice play on concepts to retain believers. Disobedience is bad, because it implies you are lacking Faith. Therefore, Doubt is equated with disobedience. The act of thinking critically about the content they are feeding you or the act of approaching the boundaries of the acceptable level of doubt is seen as disobedience, rebelliousness, and pride; Some of the worst things possible in the Christian world view. Free thought does not exist, only prideful people who think they know better than God. Critical thinking does not exist, only rebellious people who just don’t want to accept the truth. This is a perfect system for retaining believers. Especially if you have family who whole-heartedly believe it. Why would you want to disappoint your parents? How could you possibly have an open dialogue about your doubts when the very act of doubting is sinful? Doubt is something that leads to shame. It is seen as something you need to atone for. Something requiring repentance. “I am sorry my faith is wavering God”. I am not exaggerating either when I say this is what I observe in this odd little culture. They will say that “Faith is having Trust in god”, which is equivalent to saying, “doubt is an expression of distrust”. But “how could you doubt GOD, can’t you see he’s so great?! Didn’t you read the bible; he keeps all his promises!!! You’re probably just hurt or mad at god. He has a plan for us all and loves you”. On the “trust” conception of faith, doubt can only be seen as distrust for illegitimate reasons. But what happens when you doubt the very metaphysical framework upon which this god character rests? How can you “distrust” an entity you can’t perceive with any of your sense? “You just have to have faith!!!”. Round and round we go in a circle.

As alluded to in the previous paragraph, most explanations of religious doubt tend to put the blame on the doubter. In the book "God in the Dark: The Assurance of Faith Beyond a Shadow of Doubt" Christian apologist Os Guinness gives us a detailed description of how doubt is entirely the fault of the believer. It has always struck as odd that an omnipotent deity would need constant defense when it could simply cut out the middlemen and tell each of us directly. The Christian religion is literally hearsay. We have a collection of stories and are told me must simply “take their word for it”. Simultaneously, if we are reluctant to accept the absurdity, we are told we are flawed in some fundamental way, and the only way out of the hole we’ve dug ourselves is through the very thing we are unwilling to blindly accept. I’ll list out the contents of the book and briefly describe what’s going on. It will be clear that “doubt bad” and “you doubt because of you” and “you bad because you doubt”.

- Chapter 3: Forgetting to Remember – Doubt from Ingratitude: The author begins by describing that a Christian understands “What God has done for us” and that Faith becomes weakened you forget this. A striking quote that is quite disgusting, “As we fail to remember our previous situation, a slow and subtle change of heart takes place. What emerges is an attitude of resourcefulness that eventually grows into a mood of self-sufficiency and then into independence”. This is a wonderful admission of the paramount emphasis religious institutions place upon submission and obedience. Self-sufficiency is equated with ingratitude. Another quote confirms this by saying “But the key motif is ingratitude, a moral, spiritual, and emotional carelessness about what we once were and would be now apart from God”, as if it’s impossible to show gratitude if not directed towards a god. Ingratitude is the explanation for suffering in biblical stories, and independence is the chief causal factor initiating sinful behavior. The author exemplifies this by saying “Forgetfulness proves deadly because it strikes deep into the delicate area where conscience registers sin and where each of us is most attuned to the nuances of relationship. With this area desensitized, it is only a matter of time before our faith is also numbed. A spiritual movement of independence gathers force underground and comes out into the open, using doubt as its prime organ of propaganda.” In other words, ingratitude due to doubt and independence interferes with your ability to discern sinful behavior. He gives specific biblical examples where this allegedly was the case. The lesson of this chapter is straight forward; doubt couldn’t possibly arise because you find these legends fictitious or are unconvinced of the existence of a deity, it is because you are “forgetting all that god has done for you” and are blinded by your drive for self-sufficiency. Obviously, showing gratitude is important. But equating doubt with ingratitude or implying free thinkers are incapable of showing grace is just bullshit. It’s important to recognize however that these “explanations” of doubt resonate with many believers, causing them to think there is something wrong with themselves for identifying inconsistencies in the biblical narrative, or by realizing that alternative explanatory frameworks work better for describing the world. I’ll finish off this section with yet another striking quote demonstrating the sheer narcissism of this view: “This first variety of doubt is a rationalization. Contrary to what the doubter says, the problem is not in the belief but in the believer. It is not in the insufficiency of truth but in the ingratitude and self-sufficiency of the truster. In essence, this doubt holds nothing against truth except that it is inconvenient. It may express itself extremely vocally and raise a wide range of objections to the truth, but these are not genuine doubts. They are part of the propaganda exercise of doubt itself. The real bone of contention is that truth is unnecessary and unwelcome rather than untrustworthy.” In other words, it’s not a problem with our unsubstantiated belief, it’s a problem with you. Imagine if science and engineering worked this way. Imagine if I used this as a framework for convincing others. Guilt and Shame work wonders, “look at all we have done for you, such an ungrateful wretch, you deserve nothing but eternal torture”.

- Chapter 4: Faith out of Focus – Doubt From a Faulty View of God: We can see again by the title that the doubter simply “can’t understand the true nature of god”. Immediately out of the gate, the possibility of God being what he seems to be at face value reading the old testament, must be swept aside. Or the Problem of Evil/suffering must be swept aside. Or the problem of divine hiddenness must be swept aside. All our seeming’s are simply because we cannot see the god that the author has the fortune of being able to see. The author begins by describing how it’s possible to misunderstand someone based on polluted preconceptions, which manifests as prejudice, thus hindering the relationship. The author claims “Since they do not recognize what they are doing, they blame God rather than their faulty picture, little realizing that God is not like that at all. Unable to see God as he is, they cannot trust him as they should, and doubt is the result.” Presumably, the author means to say that his view of God is not faulty, it is the true conception. The problem should immediately be apparent; this argument can simply be used against itself to claim that the author has a faulty view of god. It is entirely self-defeating, and this inconsistency follows from the author’s first explanation of doubt. He claims that faulty presuppositions can distort the view of god. Well, if “turning to Christianity” is in part a function of the perceived need for salvation, is it not possible that this creates an unjustified presupposition of a god? Does the believer simply impose their conception on to god because of the acute psychological tensions arising from existential dread? There is no reason a-priori to accept the theistic view of a personal god, even if we grant the possibility of a Creator. But no, none of this could possibly be considered. Furthermore, the author claims that a lack of “Christian presuppositions” distorts our view of the god conceptualized by Christianity. This is a striking admission of what I’ve alluded to throughout the prior posts. For some of these ridiculous arguments, apologetics, and biblical narratives to even begin to appear plausible, you must be primed and lead to them in very particular ways, thus creating “Christian presuppositions”. But there is nothing wrong with questioning these presuppositions. In fact, if they cannot withstand scrutiny, we should be reluctant to accept them as valid. One “presupposition” that is philosophical in nature is Substance-Dualism. Without this, the entirety of Abrahamic Religion becomes obsolete. Another “presupposition” is the view of divine revelation; god chooses to selectively reveal the truth to some people and not others. What if the doubter begins to question the notion of revelatory religion? Another concept that always seems to be overlooked is Free Will. What if someone identifies the problem of divine foreknowledge and its implications for Free Will, finding apologetic arguments absolute bullshit and new doctrines like “open theism” implausible? The author is correct in one sense; to be a Christian means to overlook the inconsistencies inherent to the religion. The apologetic tactic implicit in this section is clear: “disagreeing with my conception of god or questioning my conception of god happens because you are flawed, not because I haven’t substantiated any of my claims”, shifting the blame onto the doubter. But the problem is even worse when we really dive into it. The author says “But if our picture of God is wrong, then our whole presupposition of what it is possible for God to be or do is correspondingly altered. When the presuppositions are wrong, the picture is wrong. Faith is out of focus, God is not seen as he is, and in this field of badly focused vision, with its dangerous loss of clarity or completeness doubt easily grows. Such doubts are the direct result of a faulty picture of God. Notice exactly where the problem lies. This type of doubt is not a matter of doubting the right presuppositions but of believing the wrong ones. That is an important difference.” The problem here is that god is traditionally conceptualized is tri-omni, meaning he is capable of anything. This is the view of god we are supposed to have, so when we are facing Divine Silence, while expecting a God who intervenes, experiencing Gratuitous Evil, when told God is all-loving, or when we are identifying inconsistencies in biblical narratives, while being told god’s word is “perfect” (whatever the fuck that means), one could hardly be blamed for experiencing doubt when the manifested state of affairs is inconsistent with what preachers are spouting. The key point in the authors rambling is that you must presuppose everything points to god, everything is controlled by god, and the Christian dogma is true, to “see the true god”. In other words, you must presuppose Christianity is true, to see that it is true. No substantiation is given to the doubter. This is played out in real life in the Church across the world. Completely meaningless correlations are said to be “god working in our lives”. In fact, Christians are encouraged to interpret arbitrary, mundane, and banal events as “proof of god”, and are told to disbelieve any contrary explanation as “inspired by Satan”. The author goes on by describing two ways our “faulty presuppositions” distort the true picture of god, equating them to a “trojan horse”. The first is allowing “pre-Christian presuppositions” to remain; presumably he means some sort of naturalism. The second is by allowing “alien presuppositions” to enter the mind. So, in so many words, the author is telling us you need to suspend your critical faculties to have a proper view of god, dogmatically accepting Christian presuppositions. In other words, you must indoctrinate yourself. I’ve never experienced a book that pissed me off this much. He continues by saying that the “Christian Student” is bombarded by “relativism on the campus”. This is the fear mongering I’ve referred to in prior blog posts. I think this chapter is a clear extension of the prior chapter. Questioning is bad. End of story. The constant use of pernicious metaphors like “trojan horse” really emphasizes the idea that critical thinking is like a virus. But what happens when you stop people from thinking? You retain devote believers.

- Chapter 5 – No Reason Why Not: Doubt from Weak Foundations: In this chapter the author argues that doubt comes from not having a “rational foundation” for Christianity. I think I’ve belabored the point that silly apologetic arguments are quite far from being considered as a rational foundation, so I’ve not much to say except that it’s a farce to suggest that Christianity encourages you to “examine your faith”. The author pretty much explicitly states this in the prior chapters, and I’ve alluded to this plenty throughout this section and beyond. I experience this every week I attend church. “Truth” is literally just what St. Paul blurts out in Ephesians, based on an alleged revelation from god. They will foolishly say things like “God IS truth”. I’ve addressed this elsewhere, but this is the core of the chapter. “Rational foundations” means memorizing the stock arguments handed to you by apologists who literally approach the question as a defense. They already think they have the truth; the reasons are secondary defense mechanisms. So no, there is no rational foundation. And unsurprisingly, there is no discussion of evidence. But it should be obvious by now what the effect is of a chapter like this. Many people are concerned with holding as many true beliefs as possible. By claiming that “all truth comes from the word of god revealed in the bible”, the author, and many other apologists are suppressing doubt. The believer will say “well, who am I to question the source of truth?”. Imagine if I claimed that all truth comes from me. Anyone disagreeing with me is necessarily false. This is the message these people are projecting. It distorts the concept of truth to preserve the ideology.

I always think about how hilarious it would be if we applied this model in other scenarios like scientific research, engineering, or public policy. I will never forget one of the first seminars I attended during graduate school. Some hot shot econometrician from Princeton was applying to our university for a full-time faculty position. He was presenting some of the research completed during his dissertation. Just take a second to consider the “doubt” applied to his research from the PhD committee at Princeton. This is obviously necessary to identify inconsistencies and inaccuracies in his research, along with maintaining the reputation of the school. Was it over after that? Was he able to tell our faculty they simply need to “stop doubting him”? Not at all. I never fully understood the expertise of our graduate faculty, until I saw them completely rip apart this guys presentation. Rightfully so. Imagine if they just “took his word for it”. I remember another experience during my first code-review as a very junior data engineer. I’ve never experienced such a high level of scrutiny. The amount of justification needed to demonstrate that my feature was necessary, stable, reliable, and many other properties required for a stable system, was something I had never encountered. But again, can you blame some of the senior developers? Imagine if I pushed a bug into production, resulting in some sort of cascading failure. Imagine if I never had sufficient business justification to do the work, I would have been wasting everyone's time and money. I could have just told them they are “doubting from inquisitiveness coming from a lack of trust in my ability”. Imagine where that would have got me. Another experience I remember was a research seminar presented by a potential employee for an open position at my firm. We grilled them all day. How else are you supposed to determine whether they’re a strong candidate capable of doing the job? In all these situations, the one constant is demonstration; your position must be demonstrable, defensible, and robust to criticism. This is considered virtuous in the real world. This is how we minimize the risk associated with accepting potential bullshit. In the context of religion, all of this is out the window. It is considered unvirtuous to apply doubt and skepticism especially in situations where the apologists haven’t worked out a pre-canned response. You can pretty much guarantee the reason for this defensiveness, for these manipulative tactics designed to suppress critical questioning, is that they are defending a house of cards. They know their system of dogma is not buttressed by anything, so they build defense mechanisms to prevent believers from getting to the core of the belief system. This is how the belief persists. Throughout the book, the author wants to reassure readers that "Christianity is the most rational position". This is repeated ad-nauseum, but unsurprisingly is completely lacking justification. This is obviously another tactic used by religious institutions; repeat enough and eventually people will believe it's true. When they start to doubt, suppress the doubt with a gish-gallop of unjustified bogus arguments that are collectively inconsistent. When those are doubted, shame or fear the person into submission. But on this world view, obedience is a virtue. Throughout the history of dogmatic Abrahamic religions, attaining obedience by any means necessary is morally acceptable, without the need for justification.

Comments

Post a Comment