The Nature of Agnosticism: Part 4.2

What I wish to do here is continue with the analysis presented in the previous post. What follows is a description of core features I find pertinent in regards to explaining the phenomenon of religion. I think it represents how an agnostic might approach questions related to religiosity.

Infantilization

“Worldly” knowledge and experience are perceived as contaminants to an innocent state; they are conceptualized as corruptions of the purity of our “perfect untouched” selves as envisioned in the story of Genesis. Healthy development is sabotaged in favor of preserving our most vulnerable states: ignorance, incompetence, inexperience, submissiveness, obedience, and dependency. This is particularly apparent in the founding story of the Abrahamic Religions. Quoting from a video from Theramintrees:

“In many religions; certainly, the Abrahamic ones — infantilization is intrinsically woven into the central divine concept. The god character described in scriptural creation myths designs an immeasurably inferior species called human beings who are prevented from ever attaining the god’s knowledge, skills or understanding. Humans are kept in deliberate ignorance and obliged to obey without comprehension. The Biblical creation myth frames this diminished infantilized state as perfection, purity, innocence. This innocent state is venerated as the pinnacle of human existence. That innocence is then despicably abused. In the creation myth, the god character makes a garden paradise called Eden and creates the first man, Adam, to look after it. He then creates the first woman, Eve, to be Adam’s helper. The pair of them are left to wander round the garden where they’re allowed to eat the fruit of any tree. With a bizarre exception. The god character chooses the garden of Eden as the location for two magic trees: the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. He directs Adam and Eve not to eat from the second of these warning them they’ll die when they do. But everything’s okay. He’s created them innocent — ie, ignorant, inexperienced, and obedient. What could go wrong? Well, just about everything. A talking serpent described variously as subtle, crafty, and cunning tells the innocent Eve she won’t die if she eats the fruit. Instead, she’ll become wise like the god character. She eats — and persuades Adam to eat. And true to the serpent’s word, they don’t die and they gain wisdom. As a sign of their lost innocence, they dress themselves in leaves. The god character then punishes them for disobedience casting them from Eden before they can eat the fruit of the other magic tree — the tree of life, which would give them immortality. This creation myth illustrates why innocence is not something to be venerated. Adam and Eve were presented with conflicting statements which they weren’t equipped to process. When the serpent said they wouldn’t die he meant the mere act of eating the fruit wouldn’t instantly kill them. When the god character said they’d die when they ate from the tree he meant he would personally enforce their eventual death. In fact, it was his deliberately misleading phrasing that caused the whole problem. We can safely call it deliberately misleading because, being an all-knowing deity, he would’ve known how Adam and Eve would misinterpret it. He would’ve known that if he’d simply told them he would cast them out and let them die the serpent’s statement wouldn’t’ve conflicted with his. And of course, he knew they had no capacity to process the conflicting information they were given. They were punished for failing a test they were designed to fail. The failure lies completely with the god character. If he wanted to preserve human innocence it was his job to create an environment where it would never be jeopardized. In Biblical mythology, the omnipotent, omniscient god character was perfectly capable of creating that environment if he’d really wanted to. Having just created an entire universe he could’ve placed his magic trees out of reach on some distant planet. In fact there’s no explanation for why they even had to exist. He could’ve made humans unable to communicate with anyone but him. If he wanted to preserve their ignorance he could’ve created them without curiosity. For an all-knowing all-powerful deity there’d be many simple and obvious measures to avoid jeopardizing human innocence. The fact none of those measures were employed indicates stupidity, incompetence, negligence, or active sadism.”

This is even more obvious when you stop to consider the “Abba” terminology used to describe “The Father”; in addition to church hierarchies including roles such as pastors, priests, and bishops in which subjects are encouraged to refer to them as “father”. The sheep terminology represents the tendency to infantilize as well. We are considered to be ignorant sheep unable to possibly be self-sufficient without the need of the shepherd. There is a problem underlying this power dynamic; authorities are actively attempting to sabotage personal growth and development by subjecting people to subordinate relationships. Coincidentally, one of the cardinal virtues within the Christian ethos is to unquestioningly accept authority and hierarchy, however unjustified. In fact, asking for justification is seen as somehow subversive and ungodly; consider the story of Job when asking why he was punished. Many of these structures are described as “necessary” for personal growth by church authorities. One example I have encountered was a Fourth of July sermon titled “Freedom through submission”, in which the notion of freedom was bastardized and conflated with authoritarianism. While it’s true that in some political theory, philosophers have argued that it’s necessary to relinquish some personal freedoms to live in a stable society with various rights protected by the state, it is not true that this is a submission to unjustified, unchecked, and non-participative institutions that require is to simply “take their word for it”. By compromising on some freedoms, we can gain more; but we are active participants in the process of establishing these norms and have the freedom to question them if we deem necessary. This is entirely contrary to biblical notions of submission.

There is a reason church authorities encourage their subjects to be “childlike in their belief”. Children do not have developed the proper critical faculties to distinguish between truth claims and obvious falsehoods. Church authorities understand this, therefore encouraging subjects to direct that sense of innocence towards the god figure. Coincidentally, the clergy, religious authorities, and “spiritual leaders” act as surrogates in place of their god. On Sunday morning when the pastor steps onto his podium, he tells the audience that “god has spoken to him” and that he is merely a vessel transmitting “the word” to the audience. So, by transitivity, questioning the preacher is like questioning god. This equates to one thing: You must be childlike in your relationships with authorities who hold unjustified stances and questioning them is equivalent to something satanic. In order to perceive God, we need to be like children in our ignorance, and listen to the voices in our head, rather than concrete empirical phenomenon.

Simultaneously, one of the most important features of our childlike innocence is stomped out; the willingness to question freely. As children, we are unaware of artificial social divisions, stereotypes, and other ideological filters that have yet to be imposed upon us. Consequently, we have an unadulterated sense of inquisitiveness that causes us to ask questions when something is misunderstood, free from dogmatic worldviews filtering “allowed” questions from “unallowed” ones. Religious authorities understand this, hence the infamous quote “Give me a child till he is seven years old, and I will show you the man” - St Ignatius Loyola. I don’t want to go deeply into specific indoctrination tactics, I think that has been covered ad nauseum elsewhere and is known outside of religious communities. I just mention this quote because it shows the thinking of many religious authorities; insulate from “worldly knowledge”, limit the range of potential experiences, and block out any sources of contention so the child doesn’t even have the possibility to have an alternative frame of reference to compare the bogus dogma to. Isolate them from alternative explanations, “filling them up” so to speak with one particular dogma that can answer a preapproved set of questions the child might have. Stray too far outside of this narrow path, and you are punished either explicitly or implicitly. Convince the child that “there is something wrong with them” when asking provocative questions. Convince the child that the act of questioning is ungodly. Convince the child that the only path to knowledge is through the religious authorities who speak on behalf of god.

In this process, the most important feature of a child is withering away, while the rest of its vulnerabilities are preserved and venerated. But this seems to be precisely what religious authorities aspire for; they play the god role, we become their sheep. Unlike more overtly abusive tactics, infantilization is often disguised as other things, like affection. The possibility of self-direction is seen as disrespectful or a threat. This is because infantilizers have their own personal needs that must be satisfied; the need to be in control and remain in a superordinate position. Self-determination, free from the influence of an external entity becomes a threat. The interesting thing about totalizing worldviews like the ones characterizing the Abrahamic religions is the sheer nihilism. I once witnessed a three-part sermon on how to cope with anxiety. You can imagine what the message was: there is only one way to achieve peace and that is through god. Pray more and realize that it can be a lot worse. Any attempt to resolve the internal conflict on your own is foolish because it won’t result in “true peace”; just a transitory state of bliss. But the feelings will come back, and you’ll be needing us. Putting aside the fear mongering tactic (the idea that the only way to experience peace and relieve your anxiety is through Jesus), the message results in somewhat of a self-fulfilling prophecy. By preventing your subjects from exploring alternative possible mechanisms, they are unequipped to handle these issues. If they remain in a state of anxiety after using the one option available to them, they somehow “aren’t doing it right”. If they begin to explore alternatives, the well has been poisoned, so they are probably thinking in the back of their head that its somehow “wrong” to lean on other sources other than god, amplifying the state of anxiety. If they alleviate their problems with an alternative method, that’s not evidence the religious authority was incorrect, the person must be lying about their solution or it’s “not actually working”. All of these scenarios attempt to lure the person back into the control of the authority who has infantilized them from the very beginning. In other words, the authorities are creating the very conditions that initialized the infantilizing relationship to begin with; an interesting fact about hierarchies in general is that they’re self-reinforcing, self-preserving, and self-authenticating. If there is a problem, the solution isn’t “here is a set of possible solutions, it might not be comprehensive so you should explore the search space yourself”, it is “you can’t possibly solve that problem unless you use our preapproved set of solutions that aren’t rigorously tested or anything”. Some very influential church authorities outright reject Psychiatric treatment, in favor of “biblical counseling”. They go as far to say that PTSD, ADHD, and Depression simply do not exist, they are clinical farces designed to hook us on drug prescriptions orchestrated by big pharmaThey go as far to say that PTSD, ADHD, and Depression simply do not exist, they are clinical farces designed to hook us on drug prescriptions orchestrated by big pharma. These “feelings” are simply the result of poor choices, poor coping mechanisms, and sin according to the twats like the one listed in that article. But this is precisely what the infantilizer needs to do to maintain control.

Another quote from the video encapsulates this mechanism: “Targets are trained to fear the outside world. Members of religious organizations are warned that the world is in the grip of evil supernatural entities. Political ideologues are taught to view non-members as either malevolent or enablers of malevolence. Citizens are whipped into divisive paranoia by corrupt governments. Instilling fear is designed to draw targets close with the message ‘I’ll keep you safe’; to encourage the voluntary surrender of freedoms and discourage targets from exploring a world they might find complex, beautiful, and engaging. As a result, members of religious and political groups cloister themselves in likeminded bubbles blocking and shunning dissenting opinions... And children grow up having never known an unsupervised moment or been allowed to develop age-appropriate self-management skills including the ability to deal with conflict without appealing to external authorities to intervene and dispense justice. The persistent diminishing nature of infantilization distinguishes it from authentic protectiveness and concern. Healthy parents don’t diminish their offspring. Healthy partners don’t diminish their mates. They don’t use their loved ones’ failures to shame them or disqualify them from further attempts. They understand that working through failure is how we develop. Healthy groups don’t restrict contact with non-members. They understand that other perspectives, including critical perspectives — can, like failure, be an important source of growth. The abusive nature of infantilizing protectiveness also reveals itself in the actions taken against people who try to opt out of it. Responses of emotional blackmail, smear campaigns, shunning, silencing, even threats of violence make it clear who targets really needed to protect themselves from.”

There is a book titled “Becoming God’s Children” which lays out a very concise and well researched naturalistic explanation of the facets of Christian belief. One of the key components of this system is the infantilization process, in fact it might be essential. According to the author

“—on the final goal of which is to infantilize the participant, to restore him mnemonically and transformationally to an idealized version of his own biological beginnings, to the period in which he was secure in the protective, loving, salvational care of a big one, a parental shepherd after whom he followed like a bleating lamb for several crucial years”.

This infantilized alternative beginning is the one characterizing Adam and Eve in the garden, becoming “born again” is one of the ritualistic rites (among others such as baptism) that believers engage in to be saved from their “corrupt biological body” (Col 3:10) (Mat 18:3). The author goes on to say “Christianity as religion, in short, is dedicated overwhelmingly, one might even say entirely, to the intellectual, emotional, and psychological infantilization of all those who turn to it, follow it, subscribe to it for what we commonly think of as ‘‘spiritual’’ reasons.” (p.11). In the next few paragraphs I will highlight some of the mechanisms underlying this infantilization process the author has identified.

At the beginning of Chapter 2, the author claims

“The religious world in which Christians participate is, in the last analysis, a wishful, utopian response to the daunting realities of our biosocial existence, namely, separation from the maternal matrix, the narcissistic wound of smallness or vulnerability within both nature and culture, and finally, of course, our demise and permanent disappearance from the universe, dust to dust”

the idea being that this infantilization process must be a response to something and a result of some basic human development. The author begins by describing the basic biological context of affection-nurturement during infancy. We are in a constant cycle of crisis-resolution with our parents, which ultimately forms into a strong parent-child relationship that ultimately becomes neurologically configured in our brains. It becomes part of our perceptual foundation to have some sort of caretaker; this is inextricably linked to our concept of “self”. The author claims that

“For a psychological understanding of Christianity, this is of the utmost importance. The caregiver is taken psychically inside and set up as an internalized presence, or object, that is integrally connected to, indeed that is inseparable from, the emerging self….. When we look within and discover what we take to be the self, our self, we discover not only a relationship, we discover not only a oneness that is ultimately a twoness, but we respond affectively to our inward perception in a manner that mnemonically recalls (among other things, of course) our early interaction with our primary provider…. Thus, we are physiologically, genetically, normally endowed with both a capacity and a predisposition to process current information along neural pathways that harbor our previous experience, including our experience of the basic biological situation, our experience of being a helpless, dependent little one in the care and protection of an all-powerful parent.”

The point is that when the Christian internally senses this divine spiritual feeling, what they are doing is recontacting these deeply internalized psychological foundations that are established during infancy, the inward caretaker relationship that yields a feeling of life sustaining anxiety relief. Divine contact feels affective because the physiological imprinting itself was the result of an affective relationship with a caretaker; one of constant saving from hunger and distress, and one that responded to their basic emotional and interpersonal needs, ultimately satisfying a basic need of attachment. The author claims

“The ‘‘mystery’’ of the indwelling (or suddenly present) Lord has existed for millennia, and still exists, because individuals are unable to see and to analyze their early, internalizing, neural development as human beings, the originative unconscious aspect of themselves that responds affirmatively, or accedes to, the religious narratives they are offered consciously as the early period gives way to the verbal, symbolic stage of their lives.”

Religious institutions complexify this basic god concept, but the core idea is that the concept itself can be explained with psychobiological factors and processes.

These primal processes are internalized and exploited by Christianity. The author quotes Erik H. Erikson;

“What begins as hope in the individual infant is in its mature form faith, a sense of superior certainty not essentially dependent upon evidence or reason. ... Christianity has shrewdly played into man’s most child-like needs, not only by offering eternal guarantees for an omniscient power’s benevolence (if properly appeased) but also by magic words and significant gestures, soothing sounds and soporific smells—an infant’s world.”

Christians are taught to see divine significance in trivial events by leveraging this basic psychological need. The author gives an example of a person stuck in a snowstorm, but who ultimately feels the presence of god “delivering” him from this situation. In a crisis, our childlike implicit memories call out to a divine father, to alleviate the state of danger. The person attributes the feeling to something supernatural; but we know these experiences can be fully constituted by these basic psychological structures imprinted during child development. The author states:

“At the center of the spiritual ‘‘narrative’’ to which we are devoting ourselves here resides the image of a loving, care-giving Parent-God Who devotes Himself, among other things, to watching over his vulnerable, dependent children, the human flock he has engendered and for which he is ultimately responsible. A genuine understanding of Christianity resides in the conscious comprehension of the manner in which its ‘‘core narrative’’ or ‘‘core myth’’ is ‘‘wired’’ directly into and emanates directly from the human mind-brain as it unconsciously and wishfully projects the implicit memory of one’s early ‘‘attachment experience’’ into the ‘‘present’’ reality in which one discovers himself. The narrative with the loving Parent-God at its center is the mnemonic retrieval of the early biological pattern of attachment through which one found or tried to find his emotional security and his physical safety in the world. The upshot? Christianity becomes an ongoing attachment narrative designed to enhance one’s inward stability, one’s calmness, one’s happiness, one’s vitality, in one’s always dangerous and always unpredictable surroundings. It serves the straightforward evolutional purpose of ensuring and increasing the effectiveness of one’s interactions with the environment by ensuring and increasing one’s inward psychological equilibrium, in reference particularly to the abhorrence of feeling isolated and alone, ‘‘separate’’ in the psychical sense we discovered in Mahler and others a few pages earlier”

To “know that god loves you” or that “god is watching over you” is to tap into this core psychological aspect of dependency derived at birth and early development. When basic neurological pathways are formed during childhood, it is an experience dependent process. These experiences are associated with strong feelings of relief from despair. When similar experiences occur, the brain “remembers” these experiences and associated feelings. The brain maps this analogy to the religious narrative, attributing the feelings with the theme expressed by the narrative. This explains why religious leaders encourage their congregations to attribute life experiences to the divine figure. That warm feeling you experience is explained by “god is watching over you”. This explanatory mechanism reinforces the basic belief. The author is essentially arguing that infantile amnesia is successfully exploited; the sense of gods presence is the reactivation of neural pathways that induce feelings experienced during infancy.

“The point is, the two major narratives, or stories, that come to comprise the ‘‘world’’ or the ‘‘universe’’ of the developing person, namely, the familial narrative and the religious narrative, are destined to inherit, to contain, to absorb, and to harbor, precisely the early, preverbal experience that resides at the core of that person’s mind-brain. The affect, the perception, the attachments and longings of the early period as they are steadily internalized during life’s first years, become the human ‘‘stuff’’ out of which the religious realm is fashioned and toward which religious practice is finally directed.”

The Christian narrative targets the ever-looming sense of separation someone feels as they become aware of the basic biological context in which we develop:

“Equally, as the familial narrative takes shape and the young person increasingly apprehends the inevitable psychic (if not physical) separation that looms as its culmination, the Christian narrative begins to assume a central, affective position in the psychic economy of the developing individual. While he must relinquish eventually the actual parent, he can retain forever the mysterious Parent-God, the supernatural surrogate whose attractive power emanates unconsciously from that very mnemonic place from which the attachment to the actual parent initially arose. As he becomes a predominantly verbal, narrative creature as opposed to a ‘‘primitive,’’ preverbal creature, lo and behold, there is his religious narrative to greet him, to offer him another loving, protective Parent, another Guide, another Nourisher, another Omnipotent Companion and Ally Whose hand he may clutch as he proceeds upon his increasingly separate way. At the affective, perceptual, synaptic level of his existence the Christian narrative presents itself as another version of and the direct successor to exactly what he has just experienced interactionally as a little one; and it derives its compelling power, its compelling timeless appeal, from precisely the direction of his implicit recollection: he can’t see the realistic, empirical link between the two stages, the two systems; all he can do is feel the connection inside; the unconscious associations impel him to judge the religious narrative as ‘‘true.’’ In other words, the narrative implicitly confirms what he’s just experienced as a person; it returns him to his familiar internalized reality at his emergent verbal level of understanding, and this fills him with the irresistible sensation that he is what he is, that no break exists in his being, that no separation will snatch him away from his inward emotional reality, or world. In the neurobiological terms that recall the early stages of our discussion, the Christian narrative permits him to map his early experience onto his ongoing and increasingly separate life. Reason, needless to say, is not there yet to question the assumptions of his supernatural outlook. He simply projects his way happily to the spiritual universe that is offered to him by his directional elders. Where the arms of the actual biological caregiver held him in the beginning, the arms of sweet Jesus hold him now. As the fleshly body of the mother recedes, the spiritual body of the Deity appears mentally to take her place. The believer will not be alone. With the help of society’s institutional promptings, and with the assistance of his capacities to imagine, to play, to create substitutes for the treasured caregiver he must gradually relinquish as he grows, his mind-brain will accord him just what his mind-brain requires for his peace of mind.”

The author proceeds to argue that this metaphorical relationship eventually becomes socialized. The existence of religious institutions and their hierarchical structures act as substitutes for the family context from which children emerge:

“Because social institutions (religion, education, occupation, marriage, and family) come to replace the ‘‘institution’’ of the early parent-child interaction, because social institutions assume a parental role, we transfer to society the feelings, the energies, the needs, the wishes, the loyalties, the loves (and frequently the hatreds) that motivate us during the early period. The social realm becomes an extension of the inner realm; it draws us, compels us, holds us through the mind-body attachment that comprises the very core of the first relationship. To a significant, even determining degree, then, our relationship with society is a transferential one.”

This dynamic forms a codependent relationship between the individuals and the religious community. “The social” is equivalent to “the religious”. The social institutions act out the basic Parent-Child relationship in the form of their organization and social roles. They act out the very functionality of the parent-child metaphor. I find this incredible because it explains the formation of pernicious ostracization tactics historically observed by church’s worldwide. It provides an explanatory account of the effectiveness of social manipulation and social pressure in these religious institutions.

“Accordingly, if our transferential relations with the social order turn out to be hostile or in some manner unhealthy, the social order does to us (or threatens to do to us) precisely what we dreaded early on as we interacted dependently with the parent: it confronts us with ‘‘the dark,’’ with rejection, separation, isolation, even death, the bogeys we discovered as newcomers when parenting was either forestalled or malignant. To lose our place in society can feel like losing our place in the arms of the caregiver, which is why we tend generally to obey the rules, or to rebel in a fashion that will not result in ostracism, in the temporary or permanent loss of everyone and everything. Let’s recall now Professor Durkheim’s contention: ‘‘The power of society over its members’’ is ‘‘what a God is to its worshippers.’’ The social and the religious go together because religious society inherits the first society, or function, as continuation of the initial social bond. The asking and the receiving that we do in Christian prayer is but a small specific instance of the way in which our early biosocial situation moves toward the wide social world, its providential successor.”

So far everything I’ve quoted is from the section describing the basic developmental context in which Christianity thrives. I’ve alluded to some of the specific methods intrinsic to the religion that exploit these basic psychological factors. The author goes into detail describing these features. Some of which include Baptism, Prayer, the emphasis on obedience (something I will write more about later), and the pastoral-congregation metaphor tracking the parent-god relationship. For the sake of brevity, I want to move on because you could just read the book. The main point is that infantilization is a fundamental feature of Christianity.

The Role of Metaphor

Understanding the role of metaphor in religious instruction is very important. Many arguments for the existence of god rely on analogies and the very concept of god is itself reliant on metaphorical depictions of the entity. This is at the root of Christian doctrine: God is characterized as a shepherd who lovingly tends to his sheep, God is a father-like figure who tends to his children, and God is the righteous judge who defines good and evil. It’s important to notice that these governing metaphors drive the very culture of religious traditions: their sense of moral obligation, expectations about the future, filial piety, and sense of “place” in the community”.

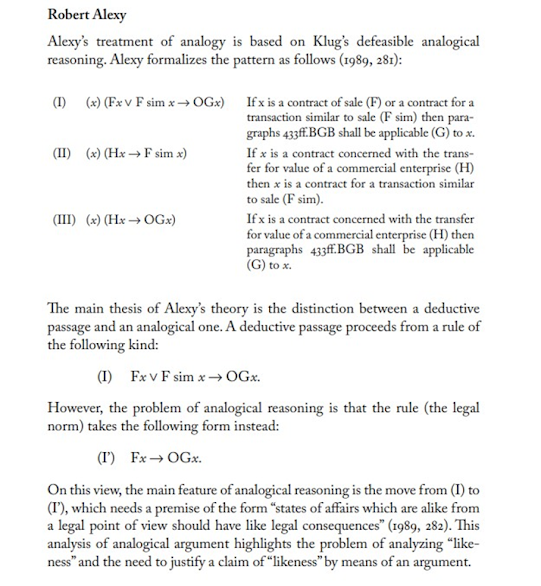

The religious mind is thus very keen and susceptible to analogies. Since it is at the core of their mental apparatus, analogy plays a disproportionate role in determining true and false statements. The key point to remember is that analogies aren’t proofs of anything; they merely suggest something. Furthermore, in the context of describing god, analogical descriptions assume gods existence; which begs the question as to how they could possibly know any properties of god to begin with. Metaphor and analogy come up often in arguments for gods existence. Before we talk about that, lets look at the argumentation structure for analogical arguments, provided by Douglas Walton.

- Similarity Premise: Generally, case C1 is similar to case C2.

- Base Premise: A is true (false) in case C1.

- Conclusion: A is true (false) in case C2.

- CQ1 Is A true (false) in C1?

- CQ2 Are C1 and C2 similar, in the respects cited?

- CQ3 Are there important differences (dissimilarities) between C1 and C2?

- CQ4 Is there some other case C3 that is also similar to C1 except that A is false (true) in C3?

- CQ5 Is there some target predicate (TP) that is true in C1, but would be absurd in C2?

- Entities a, b, c, d all have the attributes P and Q.

- a, b, c all have the attribute R.

- Therefore d probably has the attribute R.

- Entity A has attributes a, b, c and z.

- Entity B has attributes a, b, c.

- Therefore, entity B probably has z also.

- relevance of the similarities

- number of similarities

- nature and degree of disanalogy

- number of primary analogues,

- diversity among the primary analogues

- specificity of the conclusion

- Premise 1: PS is like A in S1. . . Sn

- Premise 2: A has TP

- Conclusion: So PS has TP

- The universe and a machine are similar in that both are divided into an intricate pattern of parts and subparts.

- A machine has a maker

- Therefore, the universe has a maker.

“If we look at reasoning from example in terms of genus and attributed predicate, we see that the genus is taken for granted, that is, supposed to be known in order for the text to be meaningful. For instance, in the example above, “machine” and “universe” are regarded in this context as belonging to the genus “complex objects.” In this context, the relevant semantic feature of these two terms is “to be a complex object.” The problem is that “to have a maker” is not a (relative or absolute) property belonging only to “complex objects,” nor it is a fundamental semantic feature of them, since “having a maker” is not a kind of explanation of the phenomenon. Along with this type of irrelevance, the most frequent fallacious move, especially in law, is to suppress, or to overlook, evidence. Th e main feature of reasoning from example is that the genus is presupposed, is taken for granted. The fallaciousness consists in subordinating two facts or objects to the same genus G when the description of one of the facts does not fit G’s fundamental features. In such a case, the description of the individual facts or objects is apt to suppress aspects fundamental for their classification.”

- DNA is incredibly complex genetic code

- All code must have a code author

- The more complex the code, the more intelligent the author

- The author of DNA code must be incredibly intelligent

- Therefore, the author is God

The problem with the argument should become clear. We know for sure that artificial things must have been created by something with agency because we know that it’s an artificial thing that must have been created. We have documented cases of what human design looks like. Some designs can be relatively complex, analogous to the complex objects we see in nature. But we do not know if the predicate “to be created” applies to this thing in nature, because we have no evidence or demonstrable cases of things in nature being created. To even use the word “create” in reference to the thing in nature, literally begs the question. This is why I’ve drawn a separate box and the text as a question rather than an assertion because it’s actually just a guess based on some analogy.

Anyway, human designed objects tend to avoid unnecessary complexity; in fact, the hallmark identifier of intelligence is simplicity in design. Complex structural arrangements tend not to be indicative of good design. When I submit code for review, redundant functionality and unclear structure are stripped away according to modern coding standards. Modern paradigms like object-oriented programming tend to encourage structured design patterns such as the Composite pattern, Singleton pattern, Iterator pattern, Observer pattern, and many more. In addition, there are design guidelines such as GRASP and SOLID; both emphasizing concepts such as loose coupling, the KISS principle (keep it simple, stupid!), and separation of concerns. In nature you find redundancies everywhere, it tends to not be stupidly simply, and there is high coupling everywhere. So, the underlying assumption that “the more complex the thing, the more likely it was designed by something super intelligent” just seems to be false.

- Genetic code encodes biological information through sequences of nucleotides (A, T, C, G in DNA; A, U, C, G in RNA). These sequences represent the building blocks of proteins. Computer code encodes instructions and data using symbols, keywords, and syntax defined by the programming language being used. These instructions dictate how a computer should manipulate data and perform computations.

- Genetic code operates within living cells and is executed by cellular machinery, including ribosomes and enzymes. The genetic information encoded in DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is then translated into proteins. Computer code is executed by a computer's central processing unit (CPU) according to the instructions provided by the programmer. The code is typically processed by an interpreter or compiler before execution.

- Genetic code has evolved over billions of years through natural selection and genetic drift. The structure and function of the genetic code are shaped by evolutionary processes. Computer code is designed by humans to solve specific problems or achieve particular objectives.

- The genetic code exhibits redundancy, meaning that multiple codons (sequences of three nucleotides) can code for the same amino acid. This redundancy helps to mitigate the effects of mutations. Redundancy in computer code is typically avoided as it can lead to inefficiency and bloating of software. Programmers strive for concise and efficient code. While it may evolve over time through updates and revisions, its evolution is driven by human intention and creativity.

- Genetic code adapts to changes in the environment and evolutionary pressures through mechanisms such as natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow. Mutations in the genetic code can lead to genetic variation and ultimately drive evolutionary change. Computer code is adapted and modified by human programmers in response to changing requirements, updates, or improvements in functionality. While machine learning algorithms can optimize code in some contexts, the adaptation process is guided by human intervention.

- Genetic code is represented by the sequence of nucleotide bases (A, T, C, G in DNA; A, U, C, G in RNA) in DNA or RNA molecules. These molecules are physically contained within cells and organized into chromosomes. Computer code is represented in digital form as sequences of binary digits (0s and 1s) or as text in programming languages. It is stored and processed electronically within computer hardware and software systems.

- Genetic Code can be altered by interactions with its environment, deviating from its original instruction set. Phenotypic plasticity and epigenetic changes are a few examples. Computer code cannot be altered by environmental interactions, only by some developer or hacker intervening on the system. It cannot adapt.

- Genetic code is self-replicating. Computer code cannot self-propagate.

Another way of pointing out a bad analogy is by reductio ad absurdum: you can show how there is something predicated (TP) to the primary subject (PS) that would be absurd to predicate to the analogue (A). This further illustrates how the two are very disanalogous. For example, computer code was invented around the time of Alan Turing in the 1930’s, therefore DNA was invited in the 1930’s. Another example, someone had to pay computer programmers to write the code, therefore someone had to pay god to write DNA. Or how about another: Computer programmers tend to be anarchistic in their political outlook, therefore god is probably an anarchist. One more example, computer coders require someone else to create the programming language, therefore god relied upon someone else to create the language that encodes DNA. Here is the ultimate reductio: Complex computer code relies upon preexisting stuff, therefore no creation ex nihilo. To me this method is particularly strong and just shows the fundamental weakness of reasoning from analogy in general. We should not use the structure to make assertions about reality.

So we can see that, when applying critical questioning to the structure of analogical arguments advanced by priests and apologists, they are rather frail. So why do people still find them convincing? Well, I think it has something to do with the case-by-case nature of the arguments. With analogy, there really isn’t an upward bound on what someone can decide to do. New analogies simply keep popping up. Their structures are the same, but the content differs. I think theists might not recognize the underlying structural similarity, and hence won’t pose any critical questions. This is likely because metaphor and analogy are such crucial underlying cognitive processes dictating how they understand, comprehend, and relate to the world. If you start critically questioning some of the fundamental metaphors that govern your world view, there is likely to be cognitive dissonance. Furthermore, in the case mentioned above, many people are simply ignorant about software development and genetics. It is much easier to convince someone of an analogy when they have little subject matter knowledge to identify relevant dissimilarities between the two domains. People will simply take it for granted and not ask questions. Since the capacity to generate analogy is potentially boundless, there is always something for the believer to latch on to. This is an incredibly reliable mechanism inherent to religion. It likely accounts for the fracturing of the church as well, since novel religious interpretations of scripture rely on new analogies and metaphors slightly different from a previous orthodoxy. New metaphors orient the believer’s attitude, perceptions, and energy towards different aspects of reality. The metaphor serves as an explanatory framework.

Comments

Post a Comment