Basic Considerations for Argument and Evidence Evaluation

This post will be brief. I just want to consider some useful mental tools for evaluating reasons and evidence.

Let's consider a mathematical derivation of missing evidence based on a Bayesian framework. What we want to do is show that rationally, if you cannot find evidence for some claim after a thorough search, then it is likely the event did not occur.

Definitions

- Let be an arbitrary event, or combination of arbitrary events.

- Let denote "NOT X"

- Let represent the existence of a set of positive evidences that would indicate the reality of X

- Let denote "NOT E", or the total absence of positive evidence.

- Let denote the probability of event .

- Let denote the conditional probability of X given E

By definition, this is the joint probability of X AND E divided by the probability of E:

- Let X be the intersection of two statistically independent events .

- This is follows from the laws of probability, and is a common sense view.

- The more "AND" conjuncts, necessarily the lower the probability. See the Conjunction Fallacy for more description.

Assumptions

- Event will very likely leave some type of evidence if the event occurs. The probability of E (observing evidence), given X, is greater than the probability of NOT E (missing evidence), given X. A significant event will leave evidence, if it does not leave evidence then how are we to determine whether it happened?

- If the event X is extraordinary, then all else equal, the probability of event X is very small:

- The probability of no evidence existing is high, the more we search for evidence but fail to find any, the probability approaches 1.

- After an exhaustive search for evidence, we have not found any. In the places we have expected to find evidence, we have not found any.

Invoke Bayes Theorem

From Assumption (1)

- Consider the numerator approaching zero and denominator approaching 1. Plug in

implies

Combing the terms yields

- This means that given a lack of evidence for X, it is likely that X did not occur. This shows that the probability of NOT X given NOT E will be greater than the probability of X given NOT E.

Conclusions

You can narrow down your search for explanations based on this criteria. Given a lack of evidence, you can rank order alternative explanations of the evidence. If the likelihood of X is low, and there is no evidence for X, then it follows that NOT X is more likely than X. Obviously someone will argue that X might be likely a-priori, or argue for the relevance of certain artifacts as counting as evidence. We need to argue for what is considered to be evidence; this comes prior to any probability assignment.

Within a Positive Relevance framework of evidence analysis, anything increasing the probability of a proposition is said to be positive evidence, anything decreasing the probability of a proposition is said to be negative evidence, and a neutral probability is said to be irrelevant evidence. In Bayesian confirmation theory, the standard account under which a statement is evidence for an hypothesis is positive relevance. That is, E is evidence for H if and only if: Pr(H|E) > Pr(H) and a statement is evidence against and neutral with respect to an hypothesis if and only if: Pr(H|E) < Pr(H) and Pr(H|E) = Pr(H), respectively.

In principle, we can select between competing claims based on this framework. See Theories of Evidential Relation for a more thorough discussion.

Based on this framework, one can argue that, if evidence is missing for a grand claim, it would stand to reason that the proposition is false; or at the bare minimum you should consider alternative explanations that have higher probabilistic merit. This represents the lower bound for adopting extraordinary claims.

I think this is a natural extension of the Saga Standard aphorism: "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence". This follows from a Bayesian framework: if your prior probability is low (something extraordinary, ie. incredibly implausible, is expected to have low probability relative to the ordinary), there will have to be a significant amount of evidence, or the likelihood of your evidence must approach P(X) = 1, in order for your posterior beliefs to move in a direction favorable to accepting the extraordinary claim. Intuitively, this makes sense; an extraordinary claim must have a higher burden of proof, this is almost what it means for something to be extraordinary; how else would we distinguish competing claims if both required the same proof burden? Again, based on the Bayesian conceptualization, improbable claims will need to have stronger evidence (evidence that significantly increases the posterior probability) then claims that are probable given the background conditions.

Some critical questions to consider when confronted with evidence for some claim X:

1. If there is evidence for X, is the evidence strong? Does it significantly increase the conditional probability P(X|E)? Evidence strength need not necessarily correlate with evidence amount; a single piece of strong evidence can outweigh multiple pieces of weak evidence.

2. If there is strong evidence for X, is the prior probability of X so low that it renders the posterior probability of X to be fairly low as well, even after taking the evidence into account?

3. If there is evidence for X, is it overpowered by the counter-evidence for NOT X?

4. If there appears to be evidence for X, is it understated evidence? This happens when there is generic evidence in favor of some proposition, but after consideration of more specific pieces of evidence, the generic evidence seems to understate the total evidence. Definition: This fallacy is committed when one uses some relatively general known fact about X to support a hypothesis when a more specific fact about X (that is also known to obtain) fails to support that hypothesis. For example, a prosecutor might mislead a jury by pointing out the defendant bought a knife days before the victim was stabbed, neglecting to mention that the knife purchased was a butter knife. (Paul Draper). Another Example: You see your neighbor bought a new safe car, so you conclude they must care about the safety of their children. You peer through the windows and see there are no seatbelts in the car. The initial general evidence is overridden by the more specific evidence.

Some additional considerations; there can be facts about the world that raise the probability of a hypothesis even though it's still likely false. Likewise, a hypothesis being true does not mean there is no evidence against it. We have to consider the strength of the evidence, the total evidence, posterior probability of the hypothesis, prior probability of the hypothesis, and whether there are alternative/unexplored hypotheses that have yet to be considered that could turn out more likely.

There is another aphorism that might come to mind in response to the latter: "Absent evidence is not evidence of absence". Lets consider the parable of the Turkey from Nassim Taleb's book The Black Swan. Black Swan events are incredibly rare, improbable, events with significant consequences. However, in hindsight we see them as more predictable due to a variety of reasons such as the Lucretius Problem, Survivorship Bias, Narrative Fallacy, Ludic Fallacy, Hindsight Bias and information asymmetry. The parable of the turkey shows us that, complex systems that appear stable (lack volatility), are subject to regime shifts due to black swan events, despite all of the evidence confirming the hypothesis that the system is stable. "A Turkey is fed for a thousand days by a butcher; every day confirms to its staff that the butchers love turkeys 'with increased statistical confidence'. The butcher will keep feeding the turkey until a few weeks before Thanksgiving. Then comes that day when it is really not a good idea to be a Turkey" (Taleb, Antifragile, p.93). As the turkey gains confidence in the claim "the butcher loves turkeys", the butcher surprises the turkey with an abrupt belief revision. This is a Black Swan event from the perspective of the turkey. You can think of a variety of scenarios where confirming evidence can lead you to an incorrect conclusion.

The parable shows that high confirmation causes us to be blind to the evidence that is absent. This is indeed one of the drawbacks to the framework for evaluating evidence I presented above. This is why Taleb focuses on disconfirmation; which is an extension of the notion of falsifiability. The rational approach is to seek disconfirming evidence (reduce your tendency for confirmation bias); if this evidence is absent you can have a bit more confidence in H. If you can show that the conditions needed to disconfirm your hypothesis do not hold, then you can gain a degree of confidence. The Raven Paradox illustrates the issues with confirmation: Observing objects that are neither black nor ravens may formally increase the likelihood that all ravens are black even though, intuitively, these observations are unrelated.

Hempel describes the paradox in terms of the hypothesis:[3][4]

- (1) All ravens are black. In the form of an implication, this can be expressed as: If something is a raven, then it is black.

Via contraposition, this statement is equivalent to:

- (2) If something is not black, then it is not a raven.

In all circumstances where (2) is true, (1) is also true—and likewise, in all circumstances where (2) is false (i.e., if a world is imagined in which something that was not black, yet was a raven, existed), (1) is also false.

Given a general statement such as all ravens are black, a form of the same statement that refers to a specific observable instance of the general class would typically be considered to constitute evidence for that general statement. For example,

- (3) My pet raven is black.

is evidence supporting the hypothesis that all ravens are black.

The paradox arises when this same process is applied to statement (2). On sighting a green apple, one can observe:

- (4) This green apple is not black, and it is not a raven.

By the same reasoning, this statement is evidence that (2) if something is not black then it is not a raven. But since (as above) this statement is logically equivalent to (1) all ravens are black, it follows that the sight of a green apple is evidence supporting the notion that all ravens are black. This conclusion seems paradoxical because it implies that information has been gained about ravens by looking at an apple.

Despite these problems, I think it is still possible to infer that absent evidence is indeed evidence of absence, provided certain conditions hold. Suppose you have a theory that states, under such and such scenario, evidence of type X is to be expected with high probability. You run an experiment and find that the evidence is absent. You conclude that the absent evidence confirms that the initial conditions did not hold. The interesting thing about this, is that it takes an abductive logical form, which is an extremely common form of reasoning. Consider the hypothesis that a burglar is hiding in my home. How could someone confirm this hypothesis? They can do an exhaustive search of their home, validate that entry points have not been tampered with, and maybe even acquire a hound dog to sniff out evidence imperceptible to you. Despite all of this, indeed someone can say, that absent evidence is not evidence of absence. It still remains possible the burglar is at large in your home; maybe the burglar is using an invisibility cloak, this is not impossible, do you have an evidence to suggest it is impossible? I'm sure you can start to see the issues with this aphorism; taken to its logical conclusion can lead you to a very impractical life. It is true that, the lack of confirming evidence does not guarantee that H is false; but some sort of expected evidence should be present. Below is the argumentation scheme for Abductive reasoning; you can negate the premises for the schema to fit the situation described above:

- F is a finding or given set of facts.

- E is a satisfactory explanation of F.

- No alternative explanation E' given so far is as satisfactory as E.

- Therefore, E is plausible, as a hypothesis.

And the associated critical questions:

- CQ 1: How satisfactory is E itself as an explanation of F, apart from the alternative explanations available so far in the dialogue?

- CQ2: How much better an explanation is E than the alternative explanations available so far in the dialogue?

- CQ3: How far has the dialogue progressed? If the dialogue is an inquiry, how thorough has the search been in the investigation of the case?

- CQ4: Would it be better to continue the dialogue further, instead of drawing a conclusion at this point?

There is a paper called "Arguments, Stories, and Evidence: Critical Questions for Fact-Finding" by argumentation theorists Florex Bex and Bart Verheij, that I find to be incredible useful with the analysis of evidence. Both of these scholars study the overlap between Evidence, Argumentation, Law, and AI. As indicated by the title, evidence is usually presented to us within the frame of a story; evidence is crafted in story format similar to the distinct argumentation schemes structuring common patterns of reasoning. Naturally, we can formulate a set of critical questions associated with the story, argument, and evidence to assess its merit. The stories lay the facts out in a structured order to elicit cause-effect relationships among the actors in the story; this allows the story teller to provide counterfactual accounts of the evidence and assign motive. The authors describe this framework in the context of a criminal investigation, but it generalizes to other contexts as well where stories are constructed around a body of evidence. "Key questions in a narrative approach include how to establish the coherence and quality of stories (the search for plausibility criteria), when to believe a story (the issue of justification of the belief in a story) and how to choose between alternative stories (the issue of story comparison)." (Verheij p.1). Like Argumentation schemes, Story Schemes are patterns of common instantiated stories; argument schemes are commonly instantiated patterns of argument (such as analogy, goal oriented reason, abduction, etc.), the story schemes have a structure and associated set of critical questions relevant to the story scheme being instantiated. Bex and Verheij offer a hybrid argumentative-narrative approach; the model combines elements from both frameworks, (story schemes and argumentation schemes). In the narrative approach such knowledge takes the form of general scenarios that can be seen as story schemes (Bex 2009), standard general event-patterns that act as a background for particular instantiated stories.

In the argumentative approach, arguments are constructed using premise -> conclusion format, with "Warrants" (in the Toulmin sense) guiding the generalizations. I will list more at the bottom of this post, but for now consider an example of argument from witness testimony:

- Witness w is in a position to know whether a is true or not.

- Witness w asserts that a is true (false).

- Therefore, a may plausibly be taken to be true (false).

- Was w is a position to know a?

- Is w truthful??

- Is w biased?

- Is w’s statement that a internally consistent?

- How plausible is w’s statement that a?

- Is a consistent with what other witnesses say?

- Have all of the relevant witnesses been considered?

In the narrative approach, facts are arranged into sequences of events about factual/counterfactual scenarios (called stories); the evidence is used to causally explain the possible alternative hypotheticals. The evidence is explained abductively; "The basic idea of abductive inference (see e.g. Walton 2001) is that if we have a general rule ‘c is a cause for e’ and we observe e, we are allowed to infer c as a possible hypothetical explanation of the effect e. This cause c which is used to explain the effect can be a single state or event, but it can also be a sequence of events, a story." (Verheij p.4). So in the narrative approach, we will have a set of data/evidence, and causal links represented as a directed graph, showing the sequence of events leading to the outcome, justified with abduction. Evidence by itself is atomic, it does not indicate any direction of causality; we must discern the direction of causality and this is typically done within a story schema. In the case of a criminal trial, you will be likely wanting to invoke the scheme for intentional actions presented by Pennington and Hastie (1993) "motive → goal → action → consequences"; the evidence is usually explained by reference to this story schema, but there are other variants in the literature. The idea is that the evidence will "fit" into this broader explanatory/story schema; this gives meaning to the isolated pieces of evidence, and directs our attention to the search for additional/contrary evidence. There are many criteria by which we evaluate abductive schemas " The choice between these alternative stories depends on how well the individual stories explain the evidence and how coherent (Thagard 2004) each of them is. The coherence of a story largely depends on whether the story conforms to our general commonsense knowledge of the world, that is, whether we deem the story to be inherently plausible (i.e. without considering the evidence in the case). Here, story schemes play an important role (see Bex 2009)." (Verheij p.5). The key point is that in the narrative approach, evidence is explained causally, based on hypothetical stories that "make sense" of the data better than others. It differs from the argumentative approach in that we aren't constructing arguments in support of individual pieces of evidence, rather we are holistically connecting them into a story. Many people reason about masses of evidence exactly this way.

The hybrid approach connects these two forms of reasoning about facts and evidence. In the argumentative approach, facts are justified by arguments based on evidence, while in the narrative approach facts are assessed by how well they fit into a larger story with other evidence. The hybrid approach combines these approaches; the story schemas narrate how the evidence is causally related, while the argument schemas anchor the evidence used within the story schema; unanchored evidence weakens the story. In other words, the grounding of the evidence is based on the argumentation approach while the combination of the evidence into causal stories is based on the story approach; evidence used in a story must be grounded (confirmed) by the arguments (and associated critical questions) supporting the story. Arguments that are attacked "break the chain of the anchor" so to speak, causing the story to lack evidential support. The hybrid approach gives rise to a new set of critical questions:

- (CQ1) Are the facts of the case made sufficiently explicit in a story? A case should contain a clearly phrased, sufficiently specified and coherent story detailing “what happened”.

- (CQ2) Does the story conform to the evidence? a. Is the story sufficiently supported by the evidence in the case? b. Is the story contradicted by evidence in the case? In general, not all elements of a story can be supported by evidence. This does not need to be a problem, and is in fact unavoidable as certain story elements must by their nature be indirectly justified. When an element of a story is not supported by a piece of evidence (in a given argument), we speak of an 'evidential gap'. Some gaps can be inferred from other facts, depending on the strength of the other evidence.

- (CQ3) Is the support that the evidence gives to the story sufficiently relevant and strong? a. Are the reasoning steps from evidence to events in the story justified by warranting generalizations and argument schemes that are sufficiently strong and grounded? b. Are there exceptions to the use of the generalizations and schemes that undermine the connection between evidence and fact (based on the Toulmin framework, assessed by critical questions)?

- (CQ4) Has the story itself been sufficiently critically assessed? a. Is the story sufficiently coherent? Are there required elements missing? Are there implausible events or causal relations? Is the story inconsistent? Here coherence has a specific meaning, namely that the story fits our knowledge and expectations about the world we live in. In other words, a story should be complete (i.e. have all its essential parts) and plausible (i.e. have plausible causal relations) b. Have story consequences been used to test the story? In other words, are there implications from the story we should expect to observe if the story were true?

- (CQ5) Have alternative stories been sufficiently taken into account? a. Has a sufficient search for alternative explanations been performed, not only in the investigative phase, but also in court? b. Are there good reasons to choose one story over the alternatives? Have the alternatives been sufficiently refuted?

- (CQ6) Have all opposing reasons been weighed? Have all considerations that are used to weigh opposing reasons been made explicit? Has this been done both at the level of individual facts and events and at the level of stories?

If you are interested in this type of research check out Analyzing Stories Using Schemes by F.J. Bex, Anchored Narratives in Reasoning about Evidence, and Towards a Formal Account of Reasoning about Evidence: Argumentation Schemes and Generalizations.

So far we have been discussing evidence in general without specifying a specific domain. What follows next refers to the evaluation of statistical evidence at a very high level.

What happens when we have masses of statistical evidence with varying levels of strength and differing methodologies? Reasoning through issues involving conflicts of evidence is challenging. The answers that we seek may not always be available. In general, one can look to the evidence hierarchy for guidance in weighing factual claims. Below are some considerations in the evaluation of conflicting evidence. An important realization that all studies are not created equally and that conclusions drawn from better study designs will trump those of weaker designs. However, it is important not to be dogmatic about this. The best study to back a warrant is the one that most closely matches the claim being made; there is a correspondence between the strength/generality of the claim and the proper research design. The deliberation of the relative merits of different study designs takes place within the context of rebuttals; when people can pose critical questions targeting different assumptions and design decisions. Take a look at the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to understand how to summarize masses of information resulting from intervention and observational studies. You can also check out the PRISMA statements regarding proper meta-analysis. Or any other reporting guidelines framework; in my opinion these checklists are good starting points for critical questioning.

- What is the current state of knowledge on this topic? Remember that evidence is often incomplete.

- Is reliable information available from the research literature? Is so, what kinds of studies are there?

- How extensive is the literature?

- Is there a critical appraisal guideline?

- How much of the argument depends upon factual claims (what is the case) and how much upon normative claims (what one therefore ought to do).

- How well supported is the inference from fact to value or action?

Consequently the following general rules can be developed:

- In assessing the strength of an argument that uses empirical claims one must first determine the type of study that is being cited.

- Once the study design has been clarified consult the evidence hierarchy and locate the study design. In general, more credence can be given to designs higher on the hierarchy. Hence a well-executed systematic review is more reliable than a single randomized trial. A cohort study is more reliable than a case-control study. There are many exceptions to this rule.

- If a randomized trial does not exist, this does not mean that there is no good evidence to back a warrant. Be careful of what standard of proof you are looking for and do not look for what is not or cannot be there.

- The context of the argument can often indicate the strength of evidence required.

- Always assess arguments for unstated assumptions that relate factual claims to action or belief claims.

This is just a starting point. Evidential reasoning and evaluation is a rich topic. I will end this topic with a quote and working definition of evidence from The Evidential Foundations of Probabilistic Reasoning by David Schum: "In any inference task, our evidence is always incomplete, rarely conclusive, and often imprecise or vague; it comes from sources having any gradation of credibility. As a result, conclusions reached from evidence having these attributes can only be probabilistic (and fallibilistic , my insertion) in nature. Probabilistic reasoning requires many difficult judgements in the process of establishing the credentials of evidence in terms of its relevance, credibility, and inferential force. No evidence comes to us with these credentials already established".

"Achinstein provides several interpretations of evidence including one he favors (1982, 322-336). He says that e is potential evidence on hypothesis H if and only if (1) e is true, (2) e does not make H necessary, (3) the probability of H on evidence e is substantial, and (4) the probability of an explanatory connection between H and e is substantial. Achinstein's characterization is valuable because it summarizes several points about evidence that we must examine quite carefully. First, we will often have uncertainty about whether or not the evidence e 'is true', and we have to be able to represent the nature of this uncertainty. In part, this will involve specifying exactly what evidence we believe we have. Second, if evidence does not entail (or make necessary) hypothesis H, this simply means that e is inconclusive; this is essentially what I (and Hacking) have stipulated so far. But assumptions 3 and 4 raise issues concerning relevance and the force of e on H and the nature of the argument or chain of reasoning that links e and H" (p. 15).

I like this conceptualization of evidence because it shows that evidence does not merely "stand on its own", you have to demonstrate why the evidence connects to the hypothesis and show that it is significant. Now on to the second topic....

Analyzing Arguments

Step 1: Clarify and Define Terms

- Get clear on terms, concepts, and distinctions operative in the argument.

- providing clean necessary and sufficient conditions of the terms may not be feasible, but if these conditions are provided then you can assess whether the conditions hold.

- Clarification helps avoid ambiguity and equivocation.

- Definitions should be illuminating, you should not fall further into vagueness. Definitions should be non-circular.

- Be aware of definition techniques.

Step 2: Formulate the Argument

- Structure the argument in premise -> conclusion form to make explicit what you are trying to demonstrate or show.

- Be sure to explicate assumptions as best as possible.

Step 2.1: Determine the Kind of Argument

Deductive: truth of premises is supposed to guarantee the truth of the conclusion. The premises are supposed to logically entail the conclusion. If all of the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true. You can evaluate these arguments by checking if they commit Syllogistic Fallacies (Formal Fallacies)

Non-Deductive: The truth of the premises does not guarantee the truth of the conclusion, but is meant merely to probabilistically (or plausibly) support the truth of the conclusion. It is logically possible for all premises to be true while the conclusion is false. Most of our arguments fall into this domain. They are to be considered defeasible (subject to exceptions).

These fall within the domain of "informal logic". This overlaps with argumentation theory as well. The logical form of the argument is insufficient to guarantee its soundness. These types of arguments are typically embedded in a dialogue; a goal-directed, collaborative communicative exchange between one-many parties. Douglas Walton suggests several forms of dialogue:

- The "critical discussion" occurs where the goal is to resolve a conflict of opinions.

- The "persuasion dialogue", broader than the critical discussion, occurs where one side attempts to prove a thesis using premises accepted by the other side.

- The "negotiation type of dialogue" occurs where the goal is to make a deal.

- The "quarrel" occurs where the goal is a better personal relationship between the parties.

- The "information seeking type of dialogue" occurs where the goal is to transfer information from one party to another.

- The "deliberation" occurs where two parties are trying to decide what action to take when prompted by a practical problem.

- The "inquiry" occurs where the goal is to prove something to a high standard.

evaluating arguments means understanding the intended relationship between premises and conclusion; knowing the structure helps with determining whether the relationships are strong and to what extent we can accept the conclusion.

Step 2.2 Find the main conclusion

- identifying the conclusion is sometimes straight forward, other times you will need to look for conclusion indicators. Sometimes within informal dialogues, conclusions are assumed and need to be extracted.

| Indicator |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Step 2.3 Find the Premises

- These are reasons upon which the speaker bases their conclusions. There are usually premise indicators, similar to conclusion indicators, that signal when a reason is being used to support or show a conclusion.

| Indicator |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Step 2.4 Put the argument in premise by premise form

- Take the premises you have identified

- list them in a numbered order

- note the logical connections between them (if applicable), and identify sub-conclusions within the argument through which your main conclusion depends.

- list the main conclusion and note its logical connection with the premises

- the form/structure of the argument you construct will depend on the type of argument you identify in 2.1

- The content of each premise must be consistent; the meaning of terms must remain stable throughout the argument.

- If you are constructing an argument by which there is no apparent structure, you need to apply the principle of charity and interpret/reconstruct the premises in the most plausible form and avoid the straw-man.

- Some arguments remain implicit; reformulate them in the most faithful way while remaining consistent with authorial intent.

Step 3: Determine whether the conclusion follows (if the premises are true)

- Given the truth of the premises does the truth of the conclusion thereby follow?

- For deductive arguments, check for logical validity. If the structure is valid, then you can move on to assessing the truth of the premises contained in the body of the argument.

- For non-deductive arguments, check the strength of the premises; do they probabilistically support the truth of the conclusion? Do they make the conclusion more likely than not, all else equal? Typically, in ordinary dialogues, we don't assign or measure meaningful probabilities; so this stage reduces to plausibility. The degree of plausibility you assign to a premise typically depends on background assumptions, so be sure to explicate the Warrants that glue your premises together.

- At this stage, we are assessing the formal/structural features of arguments. We are not yet concerned with the content of the premises. It is possible that an argument can be valid, but insignificantly increase the likelihood of the conclusion being true, in the case of weak evidence.

Step 4: Examine Each premises justification

- Now you can begin posing critical questions that assess the merits of the argument and the justification for each premise. You can identify informal fallacies(See this list for more), determine inconsistencies, assess whether the argument meets the burden of proof (depending on the type of argument), assess the strength/relevance of the evidence used to support the conclusion, identify defeaters etc.

- Again, it is important to remain charitable; ask for premises to be restated if you misunderstand, ask clarifying questions, remain intellectually curious. Do not be trigger happy and accuse your interlocutor of being fallacious unless you have reason to believe so; fallaciously misapplying fallacies is not a sign of charity or a good reasoner.

- Remember, your objective is to use argumentation to discover the truth of a claim. Overusing or underusing these tools could deviate you from the intended goal.

- See this Master List of Fallacies

Step 4.1 Assess the epistemic merits of the reasons

- Are the reasons justified or are they simply assertions?

- Are they plausible?

- Do they rest on implicit assumptions needing justification?

- Do the reasons conflict with other propositions we are justified in accepting?

Step 4.2 Assess the connection between the reasons and premises

- Do the reasons actually lend credence to the premises? Do they actually support it or are they irrelevant?

- Would the reasons only support the premise with the addition of an implicit linking claim? If so, is that claim justified? Is there an implicit warrant needing explication and scrutiny?

- If the reasons are supposed to only probabilistically support the premise, do they actually make the premise more probable?

Step 4.3 Assess the dialectical merits of the reasons

- Are the reasons question-begging? That is, do the reasons presuppose the truth of the very premise they are supposed to support (or the truth of the ultimate conclusion of the main argument)? Would one already have to accept the relevant premise or conclusion in order to be justified in accepting the reason offered on behalf of that premise?

- Ask yourself: In order to accept one of the premises, would you have had to accept the conclusion beforehand?

- In question begging, one assumes the truth of the very thing one is trying to support?

- Do the reasons illicitly shift the burden of proof? Is the person advancing the argument implying the detractor ought to retain the burden of proof after they question the truth of a premise?

- Do the reasons equally support a claim incompatible with the premise they are meant to support? Do they support a claim incompatible with something else in the argument?

Step 5: See if there are reasons to think the premises are false

- Even if the premises have justification, they can still be false. You may need to directly challenge a premise, by constructing counter-arguments. You are now trying to identify whether there are good reasons to think the premise is false.

- Look for counterexamples, rebutting defeaters, etc.

- For non-deductive argument, we are identifying whether the argument is Cogent: Strong + all true premises.

- Balance the weight of reasons bearing on the conclusion with the weight of reasons bearing on the conjunction of the premises. This part can be a bit tricky. What you need to do is consider all of the premises together (their conjunction) and ask if, collectively, they provide a significant enough force to accept the conclusion. You can do this by considering the inverse; taken collectively, do all of the counterexamples provide enough weight/force to consider dismissing the conclusion or accepting the negation of the conclusion? This has to do with how all of the reasons "come together" to provide a foundation for a conclusion.

- The same method can be applied to each individual premise. If the justification of a premise is considerably weak, given the counter-evidence/counter-examples, then we have reason to believe the premise is false. If the premise is false, this logically transfers to the conclusion of the main argument being false.

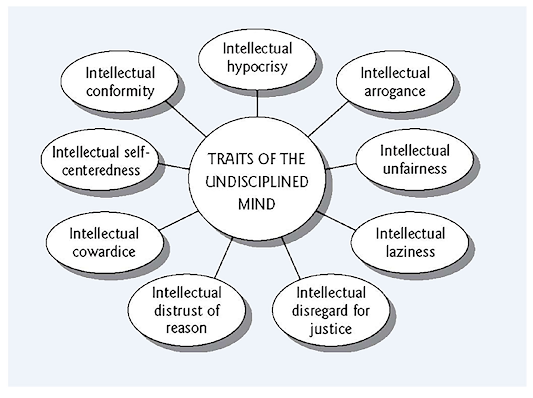

Step 6: Be Intellectual virtuous

- Argumentation should be a mutual endeavor among parties jointly trying to find truth.

- Excelling in this endeavor requires virtues - stable, habitual, excellent character traits, that orient you towards truth.

- These are dispositions that are conducive to the exchange of ideas.

- Here we are referring to behavioral traits of the individual needed to foster effective exchange.

Additional Tips

- Act as if you are on the same team. This humanizes your opponent. You are both committed to discovering Truth.

- Willingness to learn from your opponent. This is how you grow, and better understand your own position.

- Do not be afraid to say "I don't know". Be willing to live with uncertainty.

- Put truth and love center stage. Orient yourself away from "winning the debate", or any other self-centered ego-centric tendencies that can skew the pursuit of truth.

- Diversify your information sources. Do not rely on sources that only serve to reaffirm your beliefs. Be open to multiple fresh perspectives. Seek out objections to your views. Do not lock yourself in an echo-chamber. Make friends with people who have different world-views. Really try to empathize with their position and background information and circumstances.

- Explore, don't expose - rid the "game mindset". All this does is foster tribalism.

- You are not your ideas and beliefs. The moment you conflate your identity with your position on certain topics, any counter-argument (or questioning) to your position will necessarily be seen as an attack. You then get defensive and put up barriers. Your value as an individual is independent of the beliefs/ideas you allege to have.

- Put away the boxes, labels, and caricatures of the "kind of person" you are interacting with. No one fits perfectly into these pre-conceived boxes; and we certainly belong to multiple overlapping categories. We each have individual perspectives we can bring to the conversation. Do not presuppose everything there is to know about your interlocutor simply based on their group membership. All your pre-conceived filtering will do is obstruct the exchange of ideas. We are all a work in progress.

- Go slowly when analyzing arguments. Slow, methodical, systematic reflections on arguments in favor of quick "gotcha" responses to your interlocutors.

- Steelman your interlocutor, do not straw man. This reduces tribalism and reveals a commitment to truth.

- Don't psychologize or over pathologize.

- De-weaponize. Use arguments as tools to illuminate reality and collective exploration. Do not conceive of them as weapons that "defeat" your opponent.

Some additional intellectual virtues:

Now some basic argument patterns, critical questions, and considerations from the Douglas Walton paradigm. Douglas Walton proposes a classification of dialogue types that characterize common types of interactions (source). I am not sure if this is an exhaustive list, but nevertheless it's important to consider the type of dialogue you are in before applying a set of standards to the exchange. You can think of these dialogue types as broad structural features that characterize different goals and objectives for coming together with an interlocutor to speak about something. The types of arguments someone proposes will likely vary conditional on the type of dialogue instantiated. It is also important to note that Walton never claims these to be mutually exclusive; rather they can occur at different stages of a much larger dialogue and rapidly shift between different one type or another. Dialogue types can also be embedded in another dialogue type; you can imagine that within a debate there might also be information seeking.

| Type of Dialogue | Initial Situation | Individual Goals of Participants | Collective Goal of Dialogue | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persuasion | Difference of opinion | Persuade other party | Resolve difference of opinion | Understand positions |

| Inquiry | Ignorance | Contribute Findings | Prove of Disprove Conjecture | Obtain Knowledge |

| Deliberation | Contemplation of future consequences | Promote personal goals | Act on a Thoughtful Basis | Formulate Personal Priorities |

| Negotiation | Conflict of Interest | Maximize Gains (self-interest) | Settlement (without undue inequity) | Harmony |

| Information Seeking | One Party lacks information | Obtain information | Transfer of Knowledge | Help in Goal Activity |

| Quarrel (Eristic) | Personal Conflict | Verbally hit out and humiliate opponent | Reveal deeper conflict | Vent Emotions |

| Debate | Adversarial | Persuade Third Party | Air strongest arguments for both sides | Spread Information |

| Pedagogical | Ignorance of One Party | Teaching and Learning | Transfer of Knowledge | Reserve Transfer |

Being aware of the different dialogue types can help you focus your critical questions on certain features of an argument. Below are a few argumentation schemes (stereotypical patterns of reasoning) for reference:

Defeasible Modus Ponens

- Data: P.

- Warrant: As a rule, if P, then Q. Therefore, . . .

- Qualifier: presumably, . . .

- Claim: . . . Q.

Critical Questions:

- Backing: What reason is there to accept that, as a rule, if P, then Q?

- Rebuttal: Is the present case an exception to the rule that if P, then Q?

Argument from an Established Rule

- Major Premise: If carrying out types of actions including A is the established rule for x, then (unless the case is an exception), x must carry out A.

- Minor Premise: Carrying out types of actions including A is the established rule for a.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a must carry out A.

- Does the rule require carrying out types of actions that include A as an instance?

- Are there other established rules that might conflict with or override this one?

- Is this case an exceptional one, that is, could there be extenuating circumstances or an excuse for noncompliance?

Practical Inference

- Major Premise: I have a goal G.

- Minor Premise: Carrying out this action A is a means to realize G.

- Conclusion: Therefore, I ought (practically speaking) to carry out this action A.

- What other goals that I have that might conflict with G should be considered?

- What alternative actions to my bringing about A that would also bring about G should be considered?

- Among bringing about A and these alternative actions, which is arguably the most efficient?

- What grounds are there for arguing it is practically possible for me to bring about A?

- What consequences of my bringing about A should also be taken into account?

Argument from sign: Observation is evidence of existence of an event or property.

- What is the strength of the correlation of the sign with the event signified?

- Are there other events that would more reliably account for the sign? Argument from example. An example is used to support a generalization. 1. Is the proposition presented by the example in fact true?

- Does the example support the general claim it is supposed to be an instance of?

- Is the example typical?

- How strong is the generalization?

- Are there special circumstances in the example that impair its generalizability?

Evidence to a hypothesis. If A then B, B is observed, therefore A is true.

- Is it the case that if A is true then B is true?

- Has B been observed to be true (or false)?

- Could there be some reason why B is true, other than it being because A is true?

Correlation to cause. There is a correlation between A and B, therefore A causes B?

- Is there a large number of instances?

- Is there a reverse causal relationship?

- Can a common cause be ruled out?

- Are there mediating variables?

- Are changes in B due to how defined?

Cause to effect. A tends to cause B, and A has occurred; therefore B.

- How likely is B, given A?

- What’s evidence for generalization?

- Are there counteracting factors?

Waste. Don’t stop trying to realize A or all your previous efforts will be wasted?

- Could past efforts still payoff?

- Is A possible?

- Does the value of realizing A outweigh the cost of continuing?

Ethos. If a is a person of good moral character, then what a contends (A) is more plausible.

- Is “a” of good moral character?

- Is a’s character relevant?

- How strong a weight of presumption in favor of A is warranted?

Bias. Arguer (“a”) is biased, so likely has not taken evidence on both sides of issue into account.

- Is the dialogue of the type that requires participants to take both sides into account?

- What is the evidence that a is biased? Established rule. If everyone is expected to do A, then you must do so too. 1. Is doing A in fact what the rule states?

- Does the rule apply to this case?

- Are other rules involved?

- Are there reasons for an exception?

Gradualism. If you take a first step (A), you will eventually be caught up in bad consequences.

- Is A what’s being proposed?

- Do any of the casual links in the sequence lack solid evidence?

- Does the outcome plausibly follow, and is it as bad as suggested? Types:

- Causal slippery slope.

- Precedent slippery slope.

- Classification vagueness.

- Arbitrary classification.

- Verbal slippery slope.

Need for help. Person y should help person x if x needs help, and y can help without it being too costly for him or her to do so.

- Would the proposed action A really help x?

- Is it possible for x to really carry out A?

- Would there be negative effects of carrying out A that would be too great?

Resources:

2. How to Analyze Arguments Like a Philosopher

3. Dr. Graham Oppy on the Nature of Arguments

4. Pursuing the Truth: A Guide to Critical Thinking

5. Other Models of Argumentation

- Toulmin Model of Argumentation

- Scriven Model of Argumentation

- The Dialectical Method of Evaluating Argument

Comments

Post a Comment