Toulmin Argumentation Model

I was exposed to Stephen Toulmin during a second year course at University on critical thinking. This class was radically transformative; awakening me to the practice and application of critical thinking. Much of my time in school had revolved around uncritically absorbing information presented to me during powerpoint lectures, reading a textbook, or completing problem sets. After exposure to different forms of argument evaluation, patterns of reasoning, skepticism, introspection, forms of evidence, forms of explanation, certainty vs uncertainty, free thought, critical questioning, the Socratic Method, argument analysis, debating, rhetoric, higher order thinking, intellectual humility, elements of interpretation and many other features of critical thought, I became extremely confident in my thinking.

This propelled me forward in my other studies. I could actually start to see the bigger picture, how different disciplines interconnect, deeper principles governing whole academic traditions, and potential weaknesses and limitations. Rather than seeing disciplines as these abstract domains of truth bearers, I saw them as large collections of people trying to answer specific questions using evidence and reasons. Each one had specific methods accessible to them, but there was a core feature relating all of the domains (in the sciences specifically, causal relations). I too, could take part in this, in order to not only remember, but to know, and apply it to situations in my life, and even contribute. It was this explosion of potential I never knew I had. It was lurking beneath the surface somewhere in my brain, and it was not until exposure to the Toulmin model of argumentation that I started to chip away at the barrier limiting me.

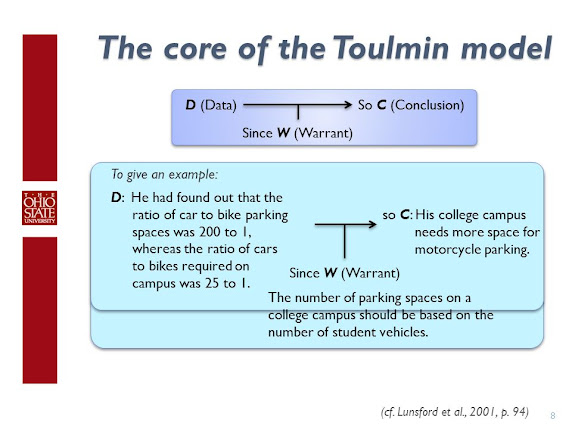

I think the main advantage of the scheme, is that it lays out a common form of reasoning in a very clear way. Lets start with the basic structure:

I don't think it is always obvious for us to probe into the reasoning behind the beliefs we hold; or why we even should. Many of us are brought up simply to think that whatever we hold to be true, is true. We are convinced, almost as a dogma, that self-doubt is inherently a bad thing. Critical assessment of ourselves is actually enlightening. This model gives us a standard to evaluate arguments. You can begin to see how you apply criticisms to others while withholding them from yourself. This asymmetry and double-standard way of thinking, for me at least, was incredible to overcome.

Many people also hold the idea that they have to commit themselves to the strongest view of whatever they think is true. Qualifying what you claim, or limiting the scope of your claim, is far from weak. It makes you more in-tune with reality. In fact, it gives you more precision and more confidence, since the true scope of the claim is preserved. In Uses of Argument, Toulmin does not intend these to be precise probability estimates. In practical argument this is almost impossible. "It may be" does not mean you have to show a probability within a 1-2% margin for example; just to show that in principle something is possible. This is amazing because it can help you recalibrate your degree of conviction; just by making explicit your warrants, backing, and data.

Here is what it looks like in practice:

The rebuttal premise is key, because it makes explicit the conditions in which your inference might be incorrect. This is important because you make it known how you can be wrong; which is intellectually humble. Your conclusion in this scenario, can be a premise or backing in another argument, or part of a larger argument in which this argument is simply a component. The key idea is that the Toulmin model shows the very basic schematic for all field-dependent reasoning. The idea of field dependency is important. Toulmin talks about how almost all forms of reasoning, with the exception of mathematics, follows this sort of pattern. The latter is characterized as field invariant.

Toulmin was a critic of absolutism and relativism. The word "invariant" means constant, unchanging, or unaffected. Field variant means that the methods of determining truth may differ vastly among chemists, children, historians, lawyers, politicians, economists etc, thus, their means of arguing and their premise. While field invariant arguments can be used in many contexts and across many fields (universal truths). So, does this mean that if the truth value of a claim depends on the context, we are subject to radical relativism? Or that if the only certainty we can gain is from axiomatic mathematical reasoning, we cannot gain any knowledge? This "dichotomy" is what Toulmin is specifically arguing against. Practical reasoning is not simply relativistic or absolutist; it has to be something else.

If you think about it, its obvious. There are different methods of determining truth in different domains. Do we apply the same standards in law as we do in scientific inquiry? It would be hard to claim that we do, and that if we do not, that both are simply relativistic. It would also be absurd to think we can apply models of deductive reasoning from philosophical logic to something like law. Normative conditions vary from field to field; this sounds a lot like Wittgenstein's language games (of whom Toulmin was a student). Think if field dependency at the level of the warrant. Toulmin's general "way of arguing" to me, seems almost universal. The warrant you instantiate, however, seems to be the field dependent component. The rules governing which generalizations or principles that are valid, appear to be contingent upon the field with respect to its origin. This also makes sense. Why is it that, someone asserting a cause and effect relationship about a medicine outside the field of epidemiology (or something) is regarded as suspect or unfounded? Well, because the field dependency is apparent. If your backing for a warrant absent any randomized trials, we have reason to suspect that the warrant is fragile.

In the introduction to Readings in Argumentation, there is a section I find illuminating.

?

Toulmin first advanced the notion of "argument fields" in his book The Uses of Argument (1958; cf. Toulmin, 1972; Toulmin, Rieke & Janik, 1979). He suggested that some features or characteristics of argument are field invariant (occur and/or are used in the same way wherever argument occurs), while others are field dependent (vary from field to field). This is an intriguing idea, and, if correct, it is useful for argument critics and theorists to identify which aspects of argument are field invariant, as well as to specify the various argument fields and the field dependent features of argument found in each. While this project may seem fairly straight-forward, two important questions arise. First, which characteristics of argument should we examine, in order to determine whether they are field invariant or dependent? Among the many choices available are: (1) components of an argument (data, reasoning, claims, qualifiers, etc.); (2) procedures (rules, presumption, order of speeches, etc.); (3) styles of arguing, and (4) strategies in advocacy. Any distinction that we can make concerning arguments and arguing could serve as the basis for inquiry into field invariant and dependent traits. However, these possibilities may not necessarily vary between different fields. That is, procedures might differ, but components might not. The field theorist or critic must decide which characteristics of argument to examine. Second, we must decide how to divide up discourse into argument fields. They could, for example, be defined by academic specialties (economics, politics, law, etc.). However, should political arguments made by politicians about, say, the annual budget, be considered to occur in a separate field from the arguments of political scientists who try to understand the budget-making process? Furthermore, would the argumentation of ordinary people about government spending and taxation be considered yet another field? Another example to indicate the difficulties inherent in defining argument fields concerns doctors and economists. When doctors argue about medicine and economists argue about economics we have two different fields. However, when doctors and economists dispute about medical economics is that a third field, or two additional ones?

So, it is not that obvious what counts as field invariant. Nevertheless, it is a really useful conceptualization when learning how to critically think. You can start to probe into how different fields establish warrants for claims. Mainly because the very question of "what makes this an argument field" enables inquiry into how the field establishes knowledge. This provides the critical thinker with a level of insight into how the knowledge is formed, to what extent the knowledge is based on clear methodology, and why some expert advice seems to run contrary to our common sense assumptions. Our warrants may conflict with those by established professionals; and we can resolve these discrepancies by asking how they came to their conclusions. The Toulmin model provides that general base to work from.

As an example, why do medical researchers tend to ignore anecdotal reports about the effect of a drug but during ordinary debate people find this convincing? Medical researchers have reason to rule this out as irrelevant when establishing the causal effect of a drug; strong arguments from probability theory and experimental design. The warrant is not arbitrary, or relativistic. This standard, however, seems to be universal to all fields interested in cause and effect; but a cause-effect relation is never "proven" in a formal, mathematical, universal sense. When a critical thinker engages with someone at the dinner table, or watches the news, or reads a politically charged news post, they can understand why certain warrants are invalid and field dependent warrants established by researchers might prove more reliable. The non expert might say something like; D: I was sick before I ate this apple, and now I am not C: Apples cure this sickness. W: My first hand experience is the most legitimate form of evidence in questions of cause and effect. The expert will say; D: Subject got sick and then ate an apple and subsequently got better. W: Experiential evidence is subject to confounding, non-reproducibility, and regression to the mean. Furthermore, we may have reason to think the anecdotal experience is biased or subject to causal fallacies. C: It is unlikely that the apple caused anything, additional research is needed.

To summarize, here are the components detailed in the Wikipedia page and some examples I found on the internet:

- Claim (Conclusion)

- A conclusion whose merit must be established. In argumentative essays, it may be called the thesis.[11] For example, if a person tries to convince a listener that he is a British citizen, the claim would be "I am a British citizen" (1).

- Ground (Fact, Evidence, Data)

- A fact one appeals to as a foundation for the claim. For example, the person introduced in 1 can support his claim with the supporting data "I was born in Bermuda" (2).

- Warrant

- A statement authorizing movement from the ground to the claim. In order to move from the ground established in 2, "I was born in Bermuda", to the claim in 1, "I am a British citizen", the person must supply a warrant to bridge the gap between 1 and 2 with the statement "A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen" (3).

- Backing

- Credentials designed to certify the statement expressed in the warrant; backing must be introduced when the warrant itself is not convincing enough to the readers or the listeners. For example, if the listener does not deem the warrant in 3 as credible, the speaker will supply the legal provisions: "I trained as a barrister in London, specialising in citizenship, so I know that a man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen".

- Rebuttal (Reservation)

- Statements recognizing the restrictions which may legitimately be applied to the claim. It is exemplified as follows: "A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen, unless he has betrayed Britain and has become a spy for another country".

- Qualifier

- Words or phrases expressing the speaker's degree of force or certainty concerning the claim. Such words or phrases include "probably", "possible", "impossible", "certainly", "presumably", "as far as the evidence goes", and "necessarily". The claim "I am definitely a British citizen" has a greater degree of force than the claim "I am a British citizen, presumably". (See also: Defeasible reasoning.)

The main point: All arguments rest upon unstated assumptions, or in Toulmin terms, Warrants. In some sense, a claim can only be comprehended, if it corresponds with a presupposed warrant. Its as if a warrant is your mechanism for making sense of new data and inferences from that data. Many people will say "The facts are the facts" or "the facts speak for themselves"; no they do not. If we agree on the facts, great. But the question is: How do you get to your conclusion? What is your glue, or process for connecting the ultimate claim to "the facts"? How does the data support the claim? This is not a question of "more" data, but the nature of the justification process. You have to show that: These facts are relevant, are enough, and the right ones to get to your claim. This is the hard part that people take for granted. This is exactly what Toulmin points out in his writings and is obvious once you lay out the structure of argument.

The Toulmin model subsumes all other forms of argument, you can literally map all forms of argument to this structure; especially defeasible ones (which I think pretty much all argument categorizes as anyway). This is so powerful; it reminds me of the universality of a Turing machine. Lets take an example of the abductive argumentation scheme from Douglas Walton and map it onto Toulmin model. To start lets make a distinction:

Abductive, presumptive and plausible arguments

- Deductive Reasoning: Suppose a bag contains only red marbles, and you take one out. You may infer by deductive reasoning that the marble is red.

- Inductive Reasoning: Suppose you do not know the color of the marbles in the bag, and you take one out and it is red. You may infer by inductive reasoning that all the marbles in the bag are red.

- Abductive Reasoning: Suppose you find a red marble in the vicinity of a bag of red marbles. You may infer by abductive reasoning that the marble is from the bag.

In this example, the abductive process can be thought of like this:

- Positive Data: the red marble is on the floor, near the bag of red marbles.

- Hypothesis: the red marble came from the bag.

- Negative Data: no other relevant facts suggest any other plausible hypothesis that would explain where the red marble came from.

- Conclusion: the hypothesis that the red marble came from the bag is the best guess.

The scheme Walton finds in the literature:

- D is a collection of data.

- H explains D.

- No other hypothesis can explain D as well as H does.

- Therefore H is probably true.

Some critical questions:

- how decisively H surpasses the alternatives

- how good H is by itself, independently of considering the alternatives (we should be cautious about accepting a hypothesis, even if it is clearly the best one we have, if it is not sufficiently plausible in itself)

- judgments of the reliability of the data

- how much confidence there is that all plausible explanations have been considered (how thorough was the search for alternative explanations)

- pragmatic considerations, including the costs of being wrong, and the benefits of being right

- how strong the need is to come to a conclusion at all, especially considering the possibility of seeking further evidence before deciding.

And a modern version proposed by Walton:

- F is a finding or given set of facts.

- E is a satisfactory explanation of F.

- No alternative explanation E' given so far is as satisfactory as E.

- Therefore, E is plausible, as a hypothesis

And the corresponding critical questions:

- CQl : How satisfactory is E itself as an explanation of F, apart from the alternative explanations available so far in the dialogue?

- CQ2: How much better an explanation is E than the alternative explanations available so far in the dialogue?

- CQ3: How far has the dialogue progressed? If the dialogue is an inquiry, how thorough has the search been in the investigation of the case?

- CQ4: Would it be better to continue the dialogue further, instead of drawing a conclusion at this point?

Lets transpose this on to the Toulmin model:

- C: Red marble came from this bag

- Q: Probably, presumably

- D: There is a red marble on the floor within the vicinity of this bag full of red marbles.

- W: It is generally not a coincidence that something found on a floor resembles the rest of a collection in a nearby bag; or was put there deliberately.

- B: Common sense, no reason to believe otherwise. Appeals to general intuition. How things "Generally work"

Now lets suppose you have some reason for overriding W and B. This is the R (Rebuttal) part of Toulmin's model, and the critical question aspect proposed by Walton. Suppose the dialogue proceeds and we find that another person was in the room, and spilled their own separate bag of marbles and didn't fully clean up the mess. Well, this overrides the original claim. This is a silly example but it extrapolates to complex cases that effect our lives.

The key idea is to start thinking about your thinking. I never really did that until introduced to frameworks for doing this.

Comments

Post a Comment